Cory60.com

Grade School

Your Online Class Reunion

|

Cory60.com Grade School Your Online Class Reunion |

|

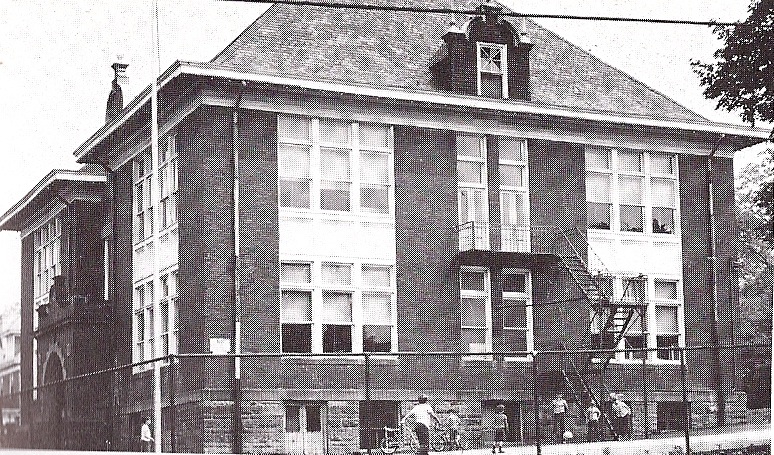

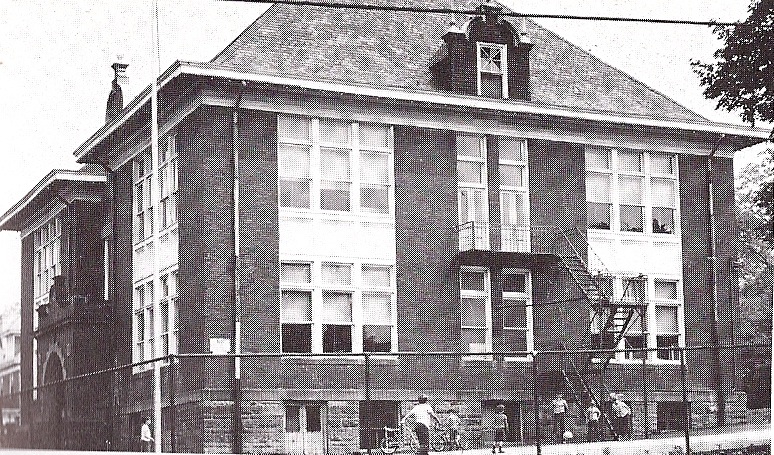

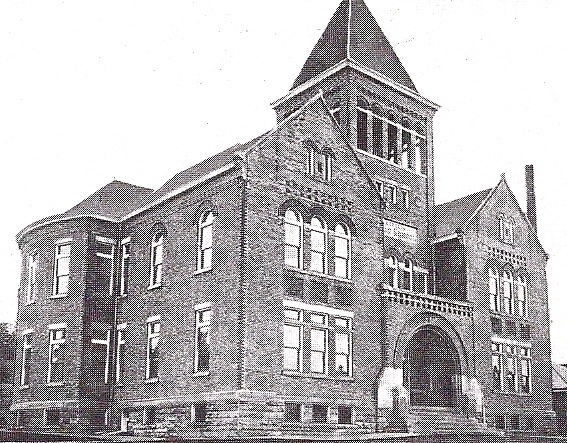

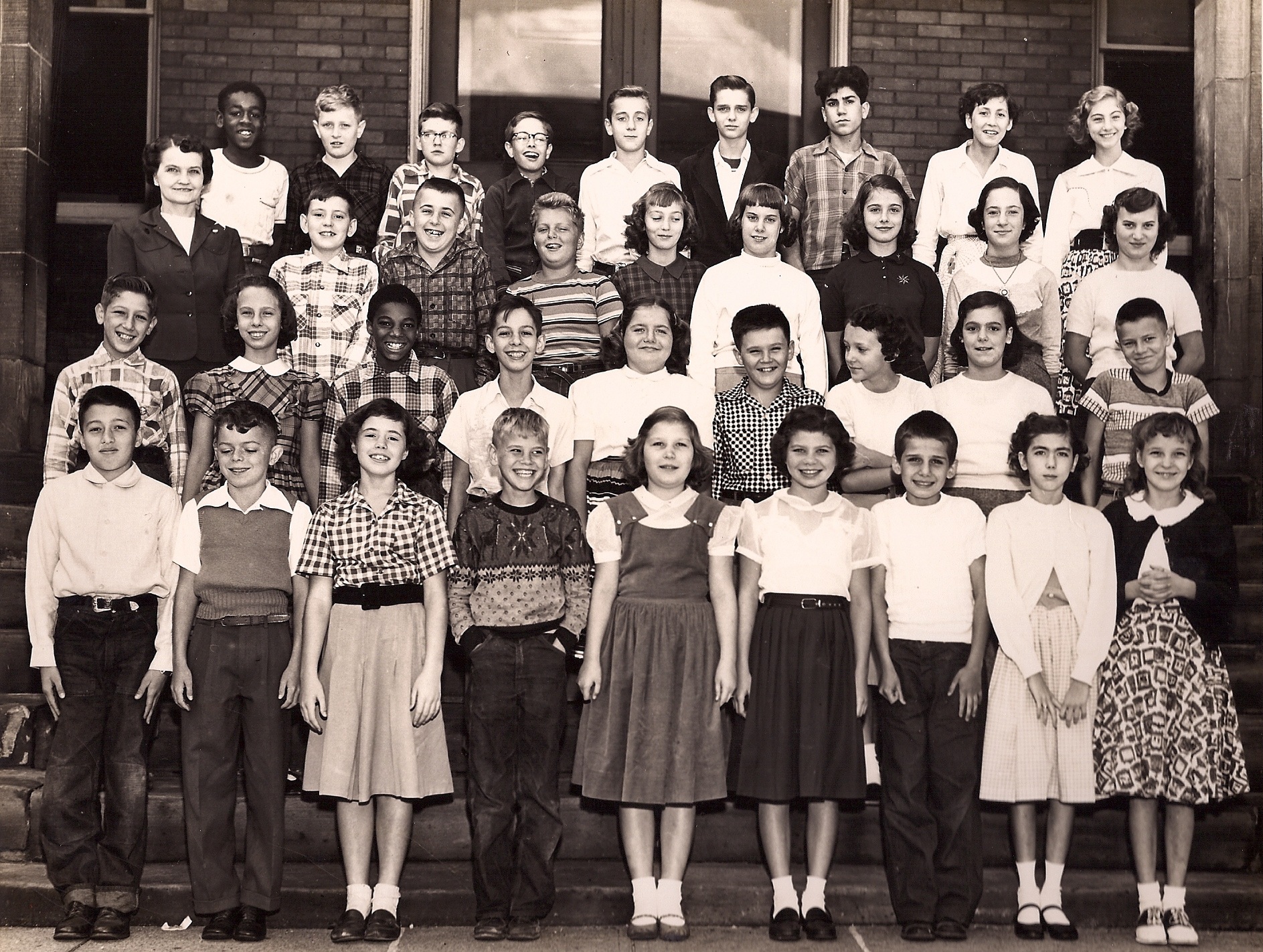

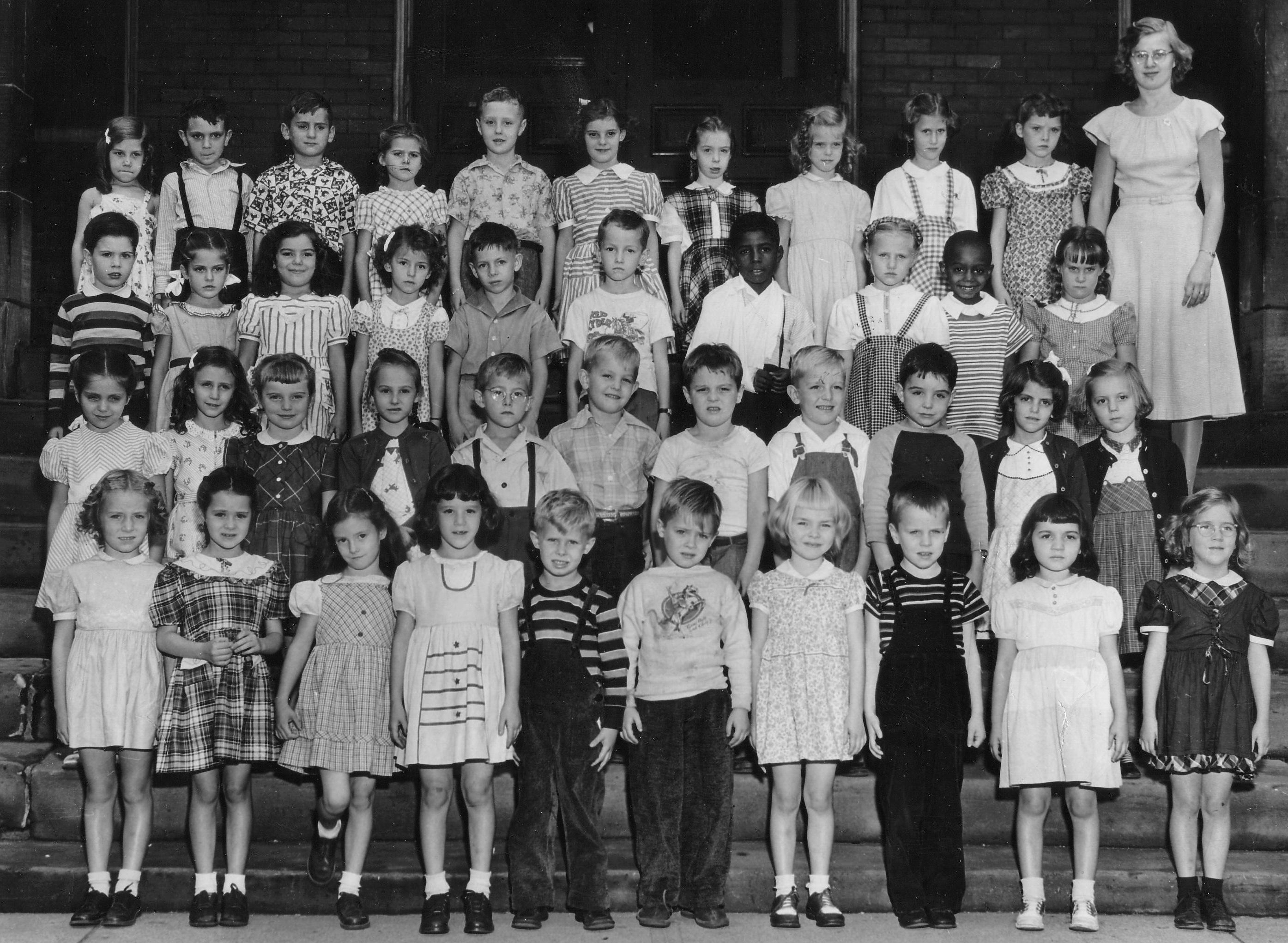

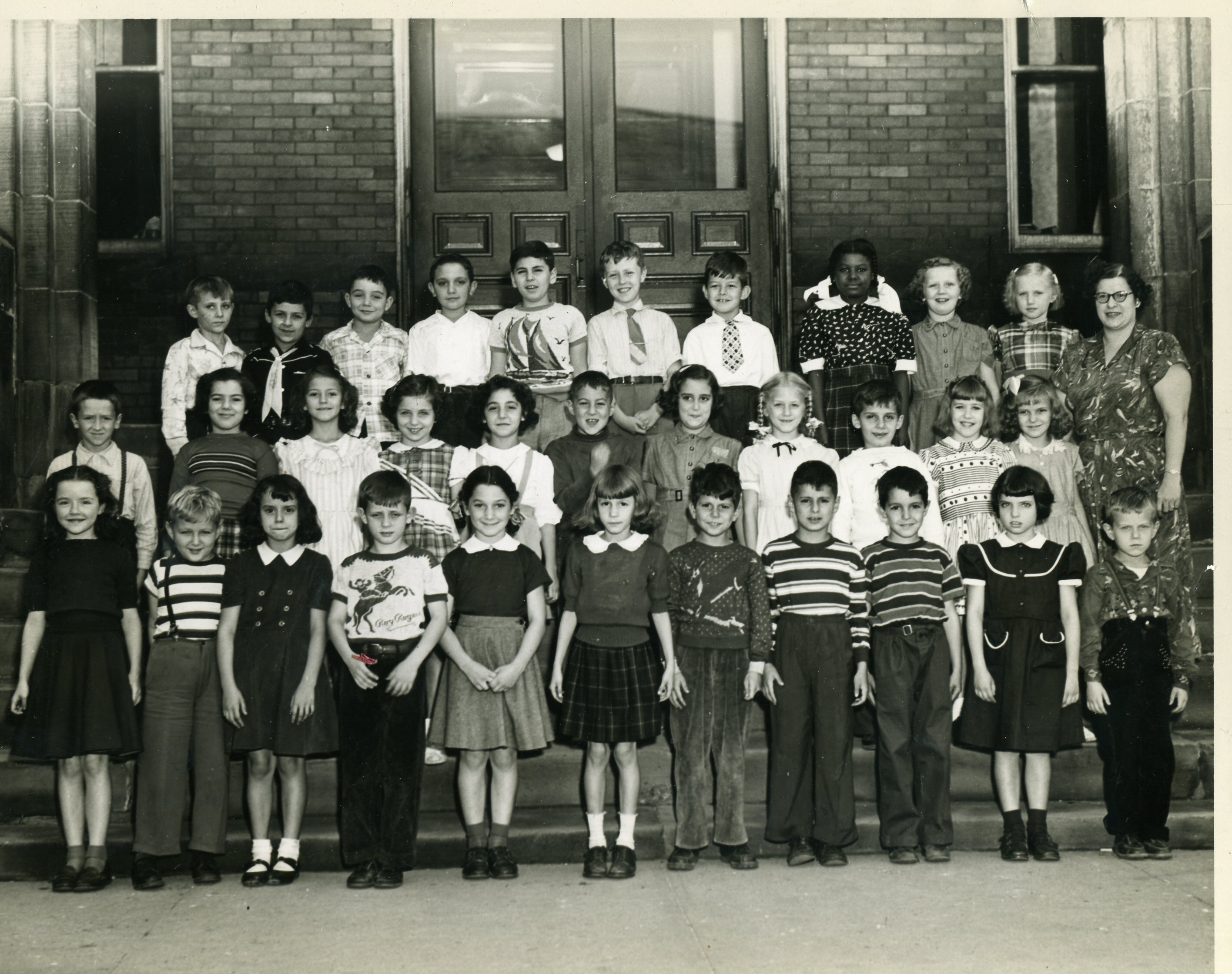

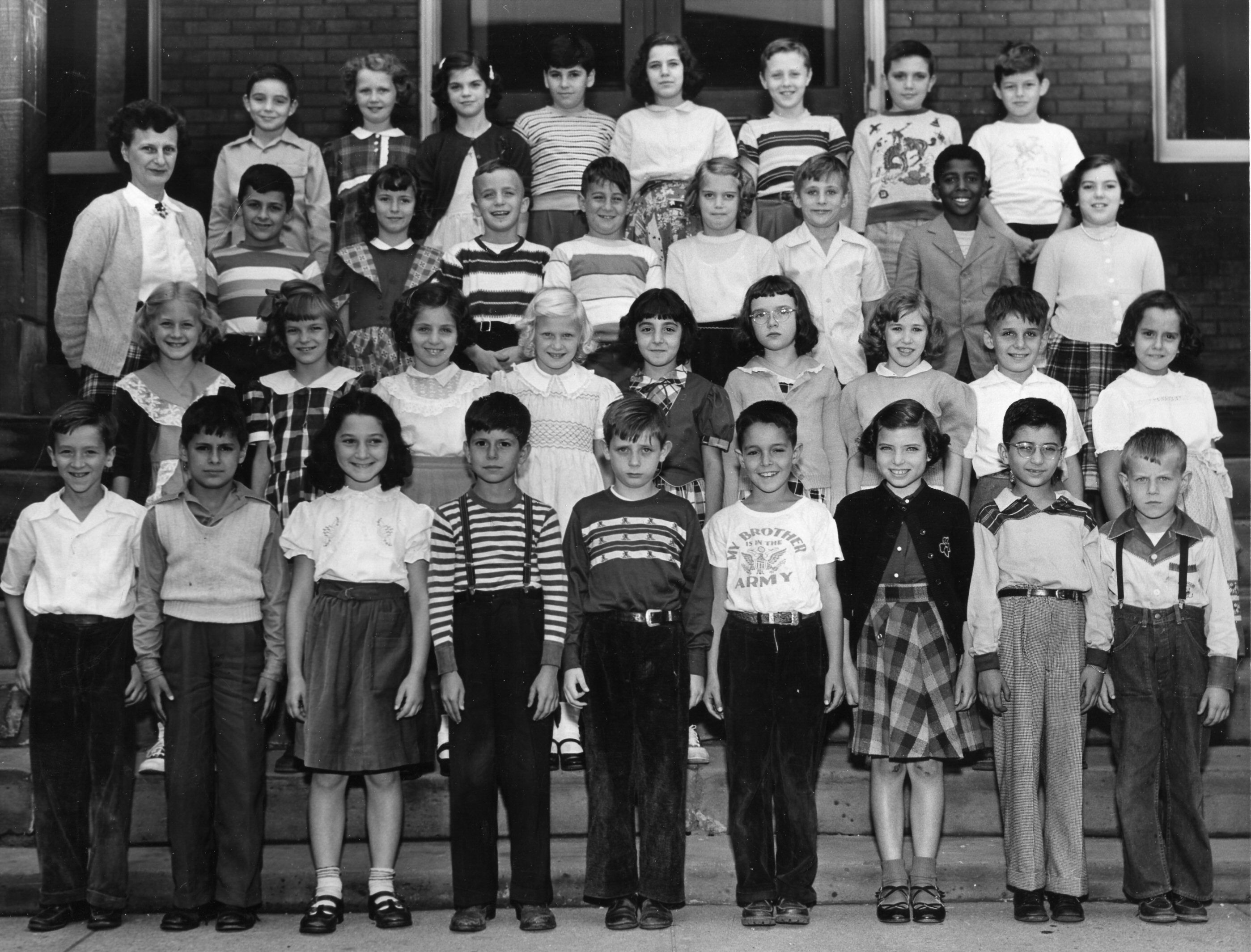

We started to school in 1948. Our first year, kindergarten, we only went half a day. At each school, the class was divided so that half of us went in the morning and half in the afternoon. This became important. We made friends in our group that we would stay close to until we graduated. Central originally housed all 12 grades, so it was the biggest building. McKinley had been voted the most beautiful elementary school in Pennsylvania when it opened. Lincoln had the biggest classrooms and largest central hallways, and because the East End of town was still being developed, it had the smallest enrollment when we entered, so Lincoln students had the benefit of the smallest classes. That would change as new streets were opened and numbers grew. Lincoln students were traumatized after fourth grade when it was announced the school could no longer hold all its students and the top two grades would be sent elsewhere. They spent fifth grade in the back wing of the junior high, then moved to the top floor of Central for sixth grade. Those were fine facilities, but many regretted for the rest of their lives only getting to attend their beloved Lincoln building for five years instead of the seven they had anticipated. |

|

|

This is not a photo of us. Many of you can find your parents in this picture. We include it because it's the best photo we have of the inside of a Lincoln School classroom. If you want to look for your parents, copy the photo to your own computer and enlarge it to a full 1000 pixels wide. However, notice the details. Notice there are 50 students in this class. Notice the huge windows, the even higher ceilings, and the large cork bulletin board back in the corner. Notice the wooden desks with their intricate cast iron scrolled bases. Notice the dark oak woodwork window frames and sills. Not shown, of course, are the blackboards across the two inside walls, and the huge cloakrooms which doubled as detention chambers for anyone who misbehaved. When Dr. Houtz took over, he was horrified at these huge classes and added sections to cut the sizes. That let him remove desks and use the added space for sandboxes, work tables, and reading corners which doubled as nap areas. |

|

|

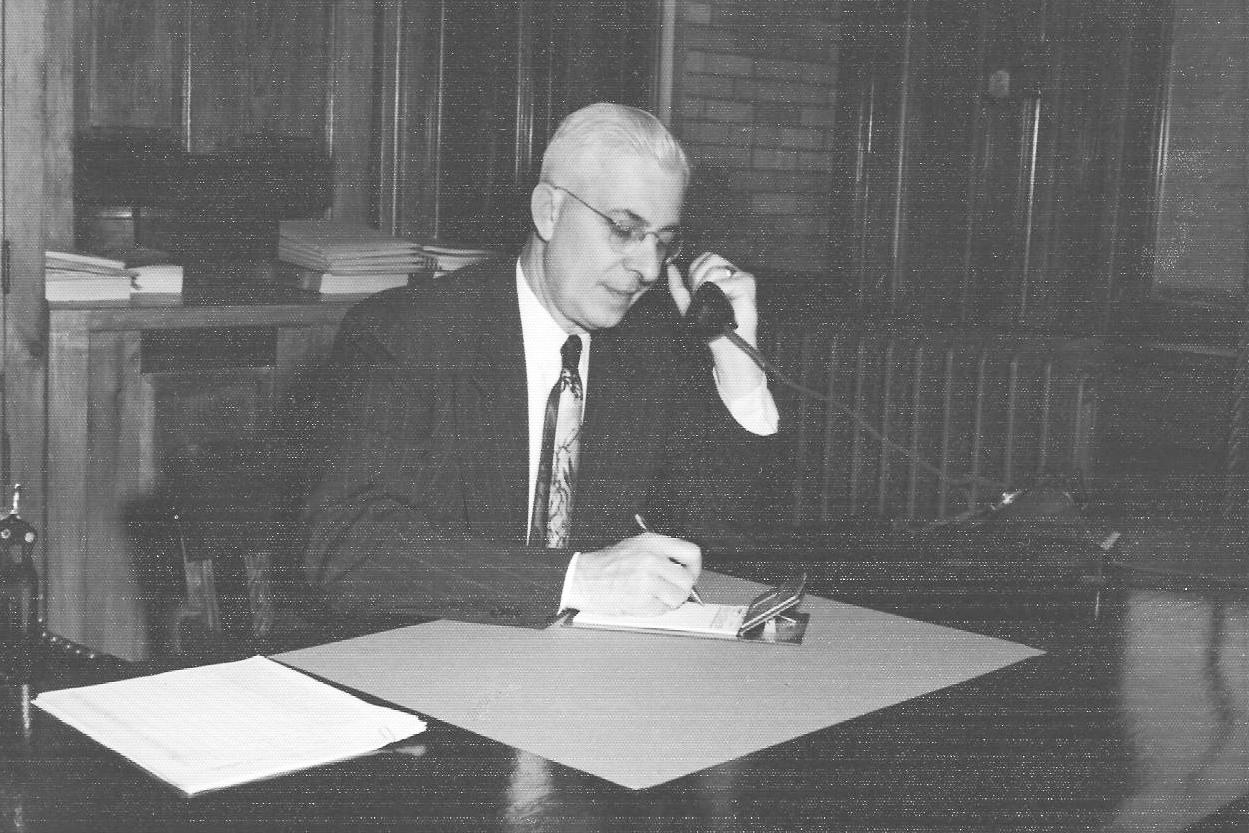

Heroes come in many guises. They don't all wear capes, masks or white hats. Some of them are the guy living down the street. We didn't know it at the time, but we were blessed to come under the influence of two legitimate heroes during our formative years. The first of these was Dr. Harry Houtz. He shaped our education from kindergarten through sixth grade. Before coaches, band directors, scoutmasters or youth directors, he was the first male authority figure any of us experienced beyond our own fathers. There was no possible reason we should have had his talent benefitting us. He was grossly overqualified to be administering elementary students. He had already been an award winning high school American History teacher, extracurricular advisor, high school principal and Superintendant of the Coraopolis Public Schools. Then, thanks to small town school board politics, he was reassigned. Given this unjust treatment, any other man would have left and accepted the superintendancy of a bigger, more prestigious, better paying system. |

Yet he stayed. He liked the town. He thought it a good place to raise two daughters. He also possessed a certain German stubbornness which would not allow a group of men to run him off. So he became Supervising Principal for Elementary Education, meaning he was responsible for all three elementary schools. Dr. Houtz was a grandfatherly figure to us, ruling the kingdom from his third floor offices at Lincoln and Central, dressing very professionally, maintaining his dignity at all times, yet quick to drop to a knee to speak on eye level to a first grader, take off his suitcoat and loosen his tie to show us a few basketball fundamentals on the Lincoln courts, or roll up his sleeves to examine our science projects.There's an old rule that "When you find yourself with lemons, make lemonade." Harry Houtz became one of the all time great examples of that. He focused his considerable intelligence on those three grade schools and set about making them the best in the state. He immediately realized that reading was the key to elementary education. And reading instruction in the forties was quite random, with each teacher basically left to her own instincts. We really did not know how to teach a child to read. Houtz designed a system retaining the old Dick & Jane books, but emphasizing repetition and Phonics. In 1948, Phonics was a radical new theory with no large scale studies to prove its worth. Houtz mapped out a comprehensive, three school study which he thought would prove Phonics was the most effective strategy. We were thus guinea pigs in a nationwide study, but it turned out to be a huge benefit for all of us. Houtz proved his point. Our class included whites, blacks, kids of all economic levels and parental education levels, kids from all religions and nationalities, and when Pitt brought in an impartial group of test administrators at the end of our second, fourth and sixth grade years we recorded Pennsylvania's highest scores. Houtz's article about how we achieved such success was published in the University of Chicago's National Education Journal. Various encyclopedias and internet sources refer to it as a "land mark study." He changed the way America taught reading, and he gave all of us the greatest foundation any group of students could have received. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

We were born into World War II. The war raged during our preschool years, and many of our parents, relatives and neighbors were in it. We were dimly aware that there was an epic struggle going on between the forces of Good vs. Evil and people we knew were on the side of Good. Sometimes it got personal. Fathers, neighbors and uncles would be wounded in faraway battles and be sent home on furlough to heal before going back to war. The Battle of Midway was a huge naval event in which 37 Coraopolis men were wounded and 12 killed. Most of the men who were wounded were manning antiaircraft guns on towers above deck and were either shot or blown off the gun turrets, falling to the deck below. Other Coraopolis men were wounded at Anzio Beach, Palermo, Corregidor, Iowa Jima, Tarawa, and Normandy. We never really understood why some of our fathers were retained in military hospitals and others sent home for a month, but even though they came home wounded we were always excited to have those months. Sometimes these medical furloughs were the only times we saw our fathers before we entered kindergarten. We knew them from photographs and letters but when they finally came home to stay they were strangers to us, men we had to get acquainted with after living with our mothers for our first five years. The War Decade had a profound effect on our growing up. Our mothers had demanded we grow up a little ahead of schedule because with no man in the house, we kids had to help with routine chores, and with no other adults in the house, our mothers talked to us as if we were older. So we entered kindergarten perhaps more mature than most five year olds. Then, when our fathers returned, they were determined to make up for lost time with us, so they were eager to volunteer to coach sports teams, teach Sunday School, help with Scout troops, YMCA Fairs, and Halloween, Christmas and Memorial Day Parades. They were also determined to make Christmases and other holidays bigger and better than usual to make up for those ones they had lost while they were on ships or in foxholes. |

| Weathermen say weather runs in 20 year cycles. If so, we were lucky. We were born into the very beginning of a 20 year period of long, cold, snowy Winters. Long before we started to school, we learned to look forward to lots and lots of snow. We could go out and play in it and get pushed around in our little sleds. We could sit inside and watch it falling. To us, snow was wonderful. We never saw it as an inconvenience, a problem, or anything to dislike. In this photo, notice the straps running under the feet, and the string connecting the mittens. Out of curiosity, we checked, and Flexible Flyer still makes this sled. |  |

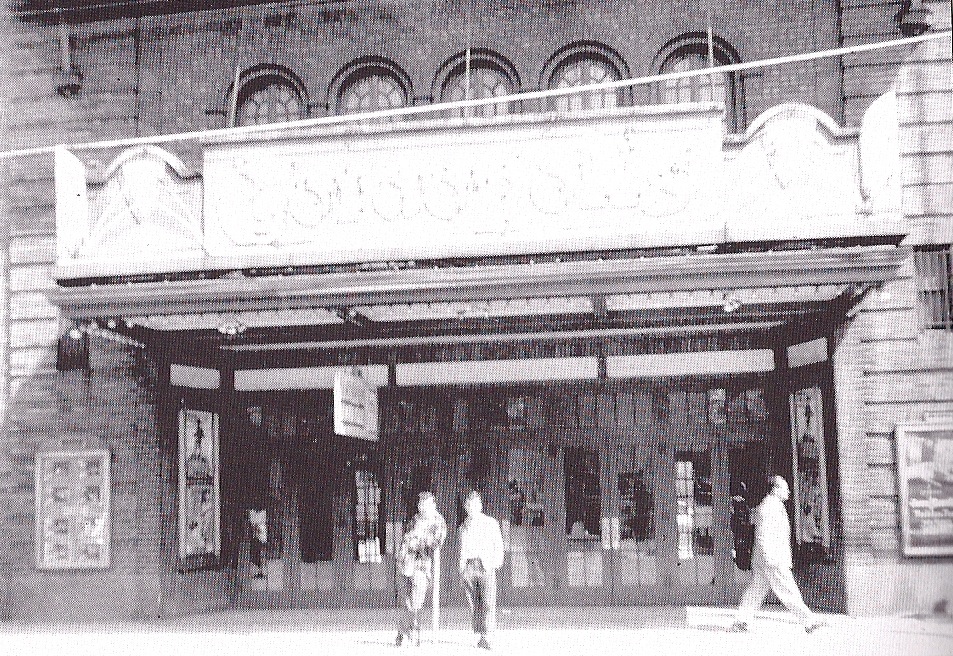

| During our kindergarten year, we became aware of the magical place downtown where our parents would occasionally take us to see a movie. Before television, this seemed to us incredible. Most of the "movies" we were taken to see during those early years were Disney cartoons. We could accurately be called the Disney Generation because we grew up on his films. During Kindergarten Dumbo the Flying Elephant reached Coraopolis, and we ran around the playground with our arms outstretched humming Come Soar With Me and imitating the chant of the magpies. During First Grade Snow White and the Seven Dwarves came and we walked to school singing Hi Ho Hi Ho It's Off To Work We Go. In Second Grade Cinderella came, which the boys tolerated by laughing at the mice, but the girls loved. When we were in grade school our children's ticket cost 25 cents. But while we always enjoyed a Friday night at the movies, none of them really had an impact on us. |  |

|

|

|

|

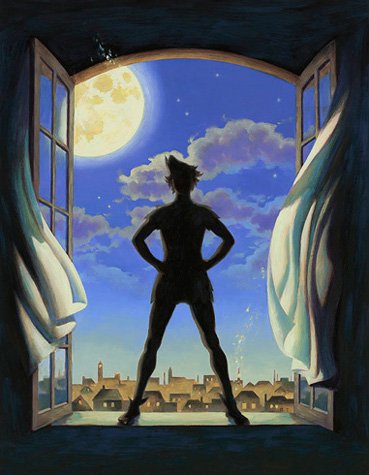

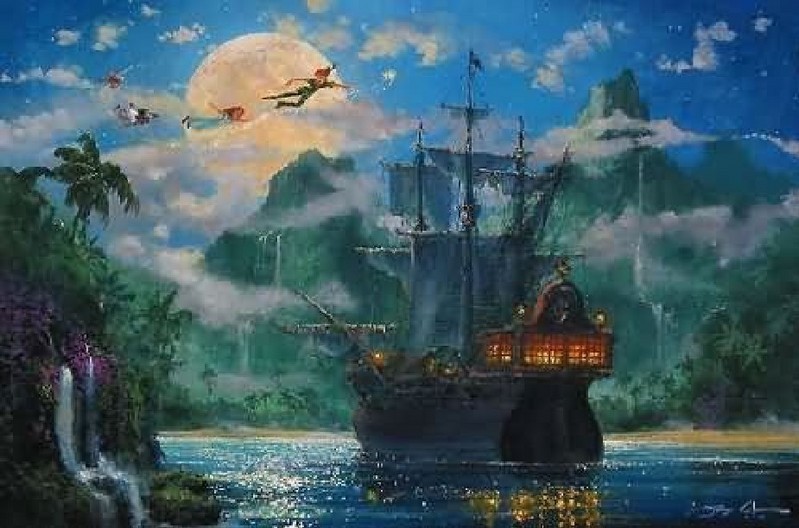

Then came Fourth Grade. The Fifth Avenue installed its new wide screen just in time for Peter Pan. The longest cartoon ever made, it lifted cartoons to a new level. It was not cute or funny. Evil, Danger and Death lurked in the shadows. We were at the right age to grasp the message: the price of growing up and whether there was some way to hold on to innocence, enthusiasm and magic. Peter Pan introduced us to Literature. The film had Meaning. Mrs. Tussey had to stock six copies of the novel because so many of us checked it out. We got to go back with aunts and sisters to see it two or three times. Later we would take our own kids and grandkids and echo the father in the film, who looked up in the sky and said, "I've seen that ship before." |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

We always were a sociable bunch. And we got an early start. Here is a group of us as rugrats posing in all our dressed up finery. How many of these characters can you still identify? |

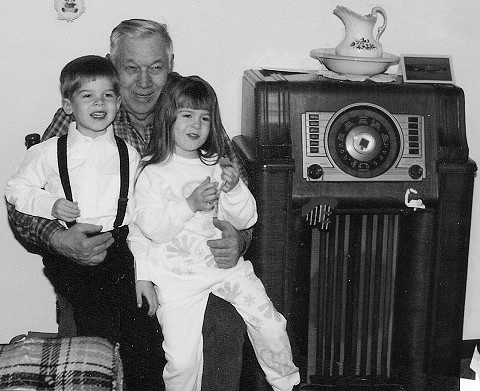

| Most of our homes had a big floor radio in the living room (right) and perhaps a smaller radio in the kitchen or bedroom. We listened to Bobby Benson & The B Bar B Riders, The Lone Ranger, Don Winslow of the Navy, and Flash Gordon. Our parents listened to I Love Lucy, Amos n Andy, The Shadow and Dragnet. Our fathers listened to Pirate, Pitt and Steeler games on the radio, and once or twice a year we'd get to go to one of their games. |  |

|

Life Below The Tracks had a slightly different flavor from life up on the hills. The three girls seated on the car here are all our classmates back in 1952. Their flat streets let them ride bikes a lot sooner and further than those of us who had to develop the strength to climb the steep hills. The river played a more important role in their lives. Many of their families and neighbors had boats docked at the foot of their streets. Every hour or so a freight train would thunder past, and while the rest of us heard it far below, it would rattle the glass in the windows of their houses. They didn't have a school playground but they had Ewing Field, which was really a complex of baseball diamond and open space. When the circus came to town it was right in their backyard. Being down on the flats, they were a long way from good sledriding, but the Fourth of July fireworks were set off at Ewing Field, so they had a front row seat from their own porches. We could go to the woods a lot easier than they could, but they were only minutes away from all the stores downtown. Where we might walk to the neighborhood store for an RC and a Moon Pie, they could walk up to Isaly's for a milkshake or a stacked cone. They had one worry we paid no attention to : flooding. In 1936 this whole neighborhood had been three feet under water. Every Spring when the river began rising, their parents were apprehensive. It never again spilled over its banks, but it was always in the backs of their minds. |

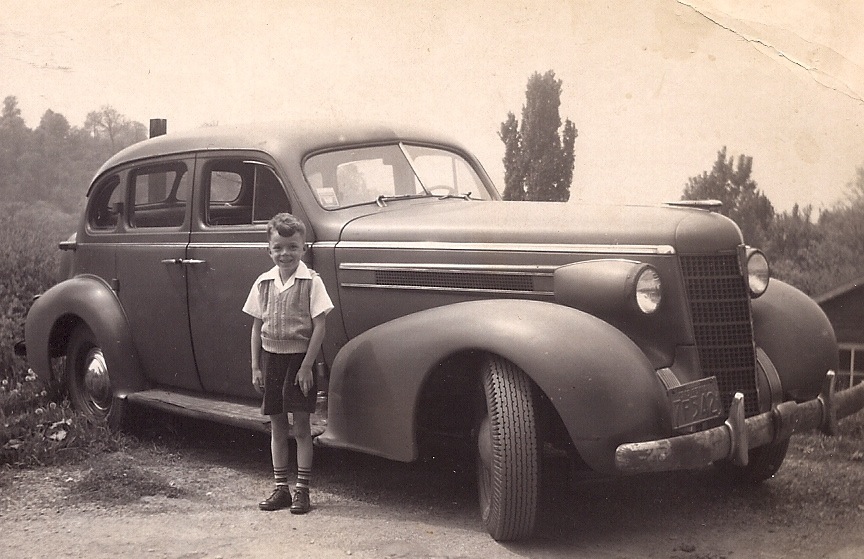

| As we started to school in 1948, our parents were driving big, heavy prewar cars. They were built like tanks and seemed cavernous inside, especially since we were all so little. There were no seat belts or shoulder harnesses and the front seats were benches all the way across. We could sit on the armrests or take naps on the rear window ledges. Nobody had air conditioning so all cars had front vent windows, triangular shapes which could be angled open to direct the air into the car as we drove down the highway. Since none of our homes had air conditioning, either, the best way to cool off on a hot Summer night was to go for a ride in the car and let that air flow over you. The big auto plants had stopped making cars during the war to convert over to tanks and military equipment. As soon as they converted back, smaller, more modern cars began to appear and these old tanks started disappearing. Most men in Coraopolis had good jobs, either in the mills or in one of the professions or local businesses. So they tended to drive Pontiacs, Buicks, Chryslers, and other middle to high end cars. But a new car cost less than a thousand dollars in the early fifties, so most families bought one every three years. |  |

|

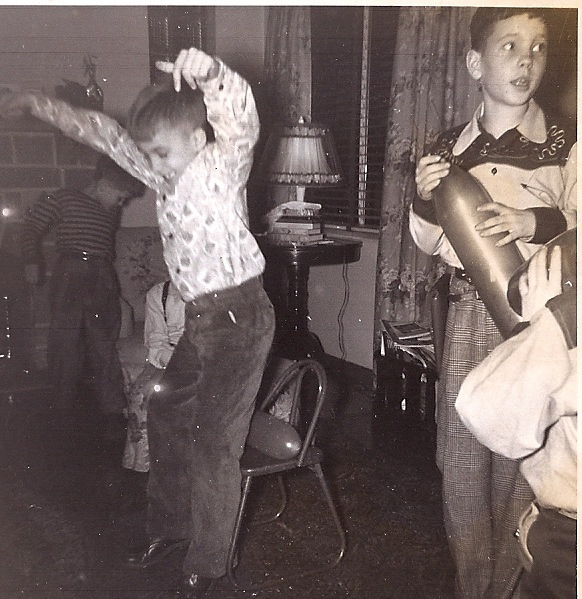

Our aunts and older sisters listened to music on 78 rpm records. Most of their record players had a crank which they turned but a few had modern electric models. The music was mostly Big Band songs featuring clarinets, saxophones and trumpets, but Glow Worm, Blueberry Hill, Mockingbird Lane and Bewitched Bothered and Bewildered were top vocals. We were vaguely aware of a new dance step called the Jitterbug, which parents and ministers denounced. Those aunts and sisters bought their records at several record stores in Coraopolis, and as we moved up through the lower grades something called The Top 40 came into being. Every Saturday KQV announced the new listings. We had to put up with our aunts and sisters listening to KQV all afternoon, which sometimes created family arguments when Pitt or the Pirates were playing and our Dads wanted to listen.

|

|

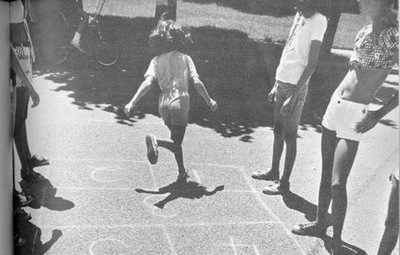

From grades 1-6 we had recess, something which seems to be dying out in schools now. At first the teachers would keep us together for coed games of Dodge Ball (something else now in disfavor), London Bridge, Hide and Seek and Softball. Eventually they let us pick up our own sides and play what we wanted. At that point the boys usually played baseball, basketball or football while the girls spent their time in hopskotch and jumping rope. That's Bonnie at left with the jump rope at Lincoln. The photo at right is not at recess; it's down at Ewing Field. But similar scenes were common on all three school playgrounds every good weather day. |  |

| While the boys were off waging crab apple wars, building dams and treehouses, and practicing sports, the girls had their own activities. One of those was dressing up in their mothers' or older sisters' clothes and posing for photos or parading up and down the sidewalk. Here is Carol, at age 8, posing in her backyard. While involved in an afternoon dress up session, the girls would also practice putting on lipstick and makeup, fix their hair in various styles, and do their best to impersonate high school or adult women.

|

|

|

This dangerous looking crew is, from left, Patty, Carol, Linda, Margaret and Penny, at a 1950 Brownie meeting. All the girls are eight years old at the time of this photo. Notice the neatly buckled belts, berets, and the handkerchiefs tucked into the pockets. Brownie units in Coraopolis were a lot more popular than Cub Scouts among the boys, but the Boy Scout units were much more active, especially when it came to outdoor adventure. As a result, while most Coraopolis girls joined Brownie units in second grade and continued on into Girl Scouts, by seventh grade most of them had dropped out, while many boys, while they didn't join until 4th grade, stayed in through graduation. As Carol put it, "If we'd been as active as the boys, I'd have stayed in, but all we did was arts and crafts so eventually I failed to see the point." |

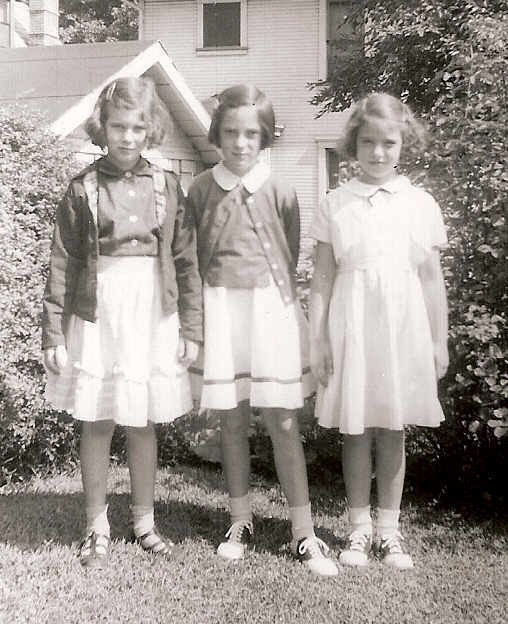

| Marilyn, Ann and Carol pause after school one day in second grade. Ann moved to Sewickley after seventh grade. She was a top student, very athletic, one of the best dancers in our Friday Night Club program, very popular, and a great loss to our class. Notice the saddleshoes on Carol and Ann. |  |

|

Before camping, before hiking and backpacking and canoeing, when we were only in kindergarten, first and second grades, many of us had our first taste of spending nights outdoors in treehouses. A fine treehouse was a great source of adventure for a bunch of kids five, six, seven and eight years old. We could fight off invading forces, sail it across oceans, pilot it to the Moon, or share it with Tarzan, Robin Hood, Peter Pan or other characters. Some of our fathers built us state of the art treehouses. Others of us built our own. The adult built versions tended to be a bit better, but they all looked good to us. The greatest tree house of all time was probably the one in the Heiningers' backyard, but there were several others in other parts of town that came close. Laying there in our kapok sleeping bags at night, we learned an awful lot about owls, bats, the moon, the constellations, wind, storms, dew, neighborhood cats and dogs out roaming backyards, and the possums, raccoons, and other animals that emerged from brushpiles and hedgerows after dark to forage in gardens. |

|

|

|

|

| The fine women of Lincoln School celebrate a birthday in Shacoski's backyard. Males sharing in the festivities are Dale (left, head on hand) and Patrick. |  |

|

|

Most of the girls in our class were Tomboys in grade school, giving the boys all they wanted in the fine arts of tree climbing, bike riding, sledriding, wiffle ball, badminton, lightning bug collecting, or any other outdoor physical activity. We lived a pre-TV, pre- video game, pre-Ipod, pre-cell phone, pre-mall existence. Our mothers would shoo us out of the house, telling us to go play and not to come back until dinner time. Girls were continually showing up with skinned or scabbed knees. And as far as the guys in our class, it would get worse before it got better. Not only were grade school girls quicker, more accurate and better balanced, but many of them grew earlier so were taller than the boys for a while. The boys would eventually catch up and surpass them, but it would take several years. This photo shows Lynette relaxing in a backyard tree near Lincoln School on a hot July afternoon. Her family would later move across town. |

| Our grade school desks were quite different from the ones our kids sat in 20 years later. Ours were screwed to the floor. The ones in first grade were quite tiny, and each year they got gradually bigger until the sixth grade desks could have held an adult. But they all looked pretty much the same : the back of each seat was also the front of the one behind it. The seat could be raised or lowered, and sometimes kids way in the back would raise theirs and sit on the edge to see better. The writing surface included a pencil slot and sometimes a hole for an inkwell, although the desks in this photo don't have those. Some years we slid our books into the desk, as the ones here demonstrate. Other years we got desks with a lift top. Some years our teachers had us rotate seats. Every week, we would move back one desk, and the week after we sat way at the back we would move to the front desk and start again. Woe be to any kid caught carving his name in his desk. He would be required to come in on Saturday and, under supervision by the custodian (Mr. McBride at Lincoln), he would sand down his desk, repaint it, varnish it and steel wool it. |

|

|

This was a desk from Mrs. Tucker's fourth grade classroom at Lincoln School the day they hauled all the school furniture out to the moving vans to truck them to Ohio. Many former Lincoln students went down to try and buy a desk or a clock for a memento, but the antique dealer who had submitted the winning bid would not sell anything that day. We later found out that each of these units brought $300 when sold by antique dealers at their shops. Central and McKinley graduates have told similar stories about trying to buy desks or clocks and being refused by the same dealer. These desks would have been used for 17 more years after we sat in them, then sat gathering dust for another year or two. Notice the ones in the photo above, which was taken during our years in grade school, are in much better condition. We were told that the cast iron scrollwork on these desks made them much more valuable. All of the Lincoln desks had this scrollwork, but most in Central did not, as seen in the photo above. Central was the original school, having been originally built to house grades 1-12 for the whole town and kids from Neville, Robinson, Moon and Crescent Townships. So its desks were older, and not as fancy. |

|

Sometimes we were more in the mood for a game of Jacks, for the girls, or Marbles, for the boys. The photo at the left is at Central, the one at right at Lincoln. Many girls would carry a bag with their Jacks ball and markers. Almost every boy carried a bag of marbles. Coraopolis boys played five different versions of marbles and when they went to other towns to visit relatives they often learned still other versions. By sixth grade we had some pretty deadly marble shooters. The boys at right are playing a fairly innocent game on a compact circle. The older boys would play in a three foot ring and winners took the marbles of the losers. Kenny, Chuck, Jimmy and Bo were the best marblists in town. Everyone enjoyed watching them play but by sixth grade few wanted to play them. We didn't realize we were honing our eye hand coordination and dexterity. |  |

The first Big World Event of our lives occurred when we were in second grade. We were dimly aware of aunts and sisters easily upset and crying for no reason. We learned the Marines had gone in to blow up the Chosin Dam to take out North Korea's electricity and end the war. It was a trap. The Chinese Communists had lured our Marines in so they could wipe them out and gain a propaganda victory. They had the Marines trapped in a long, narrow valley rimmed by steep ridges on all sides. There was no way out, no radio contact, no news. 13 Coraopolis boys were in that group, outnumbered 10 to 1. A week dragged by. Radio announcers were suggesting there was no hope. Then Saturday morning we were awakened by every church bell in town pealing. The Marines had blown the dam, emptying the Chosin Reservoir, and fought their way out, bringing their dead and wounded with them. No one from Coraopolis died. A Coraopolis native, GC Lemley, was seen in a classic Rambo like photograph coming over the hill, one wounded Marine slung over his right shoulder, another Marine leaning on his left arm, two bullet belts criss crossing his chest, a machine gun cocked and ready, and a helicopter gunship hovering overhead. It broke North Korea and ended the war. Shortly after, we saw uncles, cousins and neighbors getting off the trains in their uniforms. It was our first conscious memory of how distant events could resonate right here in our hometown. |

|

|

Once upon a time Coraopolis had an annual tradition known as the Tom Thumb Wedding. And sure enough, the event pictured at left includes our very own classmates. A lot of these characters wouldn't get this dressed up again until high school prom. Which ones can you identify? How many of our grandkids could we horsewhip into doing this ? |

|

|

|

| Carol, left, shows a little leg. With her in the backyard are Sharon, Marilyn and Judy. They're celebrating something with their luaus, but no one remembers what. |  |

|

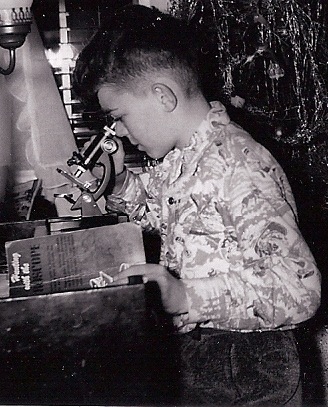

Many of us began receiving A. C. Gilbert Microscope Sets for Christmases and birthdays. None of the three elementary schools had a science lab, but by sixth grade many of us had labs at home in our basements, corners of bedrooms, or up in the attic. The Gilbert sets included a book titled "Hunting With The Microscope," which led us chapter by chapter through collecting, preparing and viewing everything from fabrics, hair, feathers, flower parts, leaf cross sections, soil samples, the microorganisms in a drop of water, blood, and every other imaginable item in our houses, backyards and surrounding woods. We wouldn't learn until college that "Hunting With The Microscope" was an all time science classic, the best guide ever written for using microscopes. Danny and Dale started studying the protozoa in McCabe's Creek, expanded that to a full scale science fair project, and with a little help from Dr. Houtz and Carnegie Tech advisors built it into a display that won local, county and state first place awards several years running. Bobby started studying the bacteria in Flaherty Creek near the Standard Steel Spring Company, shifted that to the lower part of McCabes's Creek when his family moved across town, and won a series of second places, meaning Coraopolis was dominating science fair competition in Pennsylvania based on Gilbert Microscope equipment. Every boy with a microscope set looked forward to Spring, when we could go out to the small ponds in the woods around town and collect frog eggs, bring them home, and watch them hatch and develop. It was just fun to us. We didn't realize we were learning more science on our own at home than most high school science classes teach. And this would pay huge dividends later, as many of us would earn masters and doctoral degrees in the sciences. Bobby, for instance, pursued a career in the Health Sciences. |

|

|

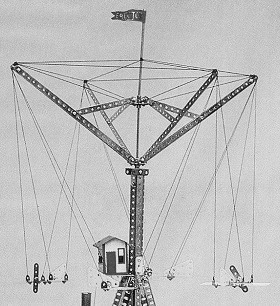

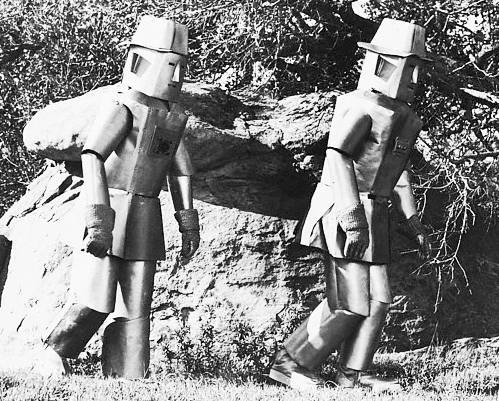

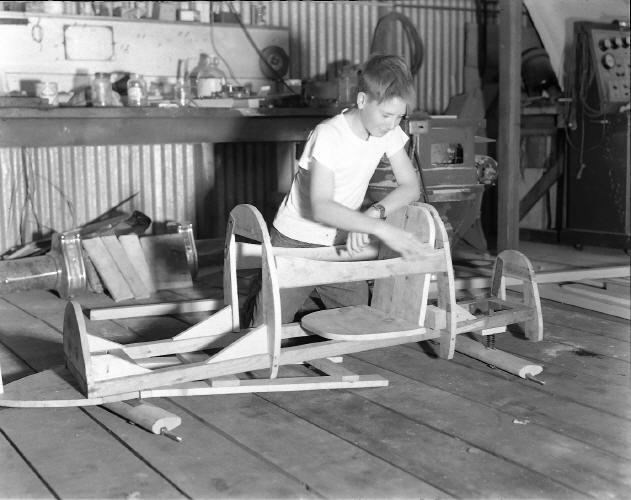

Another A. C. Gilbert product almost every boy received was an Erector Set. We could build hundreds of working models, from amusement park rides to robots and cranes. The sets came with a catalogue with hundreds of blueprints for various models, but after we built most of them, we started creating our own. Almost all of us received an Erector Set eventually, so we could exchange ideas. Every time we visited a friend's house he would proudly show off his latest model. There was both a competitive and cooperative atmosphere to this, as we taught each other techniques but tried to become the first to make some new creation work smoothly. Dale and Kenny built working models of every ride at Kennywood (below). We didn't know it at the time, but we were developing manual dexterity, visual reasoning, a knowledge of gears and electricity and basic building skills. It's interesting to speculate on how much this contributed to the high number of our class who went on to major in engineering. |

|

|

|

|

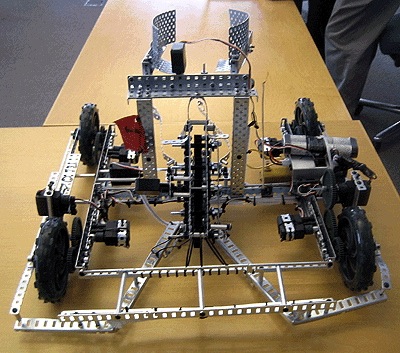

Many of our fathers subscribed to Popular Mechanics, Popular Science, and Popular Electricity. The Coraopolis Public Library had a whole shelf of books on plans for various projects. And many of us subscribed to Boys Life, which contained articles on things to build. By adding a few pieces of lumber, chains and sprockets from bicycles, and other odds and ends to our original Erector Sets we could build just about anything. This photo shows probably the pinnacle of achievement for the Lincoln School Brain Trust. It was created by Dale and Vite to run up and down the alley or around the block while they sat on Dale's front porch and controlled it from a radio transmitter. The wheels and servomotors were purchased from Kuhlman's Repair Service on State Avenue. The long U-girders perforated with holes were basic Erector pieces. Plans came from Dale's father's Popular Science Magazine. Dale's father named it Gizmo and the name stuck. We forever after called it Gizmo. It is shown here still under construction. After several redesigns and rebuilds, it could roll up to someone's front door, extend that lever in the middle, knock on the door and beep. Vite tried to enter it in Science Fair but was told while it was very impressive it was not an experiment, and it didn't prove anything. Vite said, "Well, it proves we could build it. That seems pretty impressive to me." The judges were not persuaded. |

| In addition to Microscope and Erector Sets, sometime during the 4th-5th-6th grade years almost all of us received an A. C. Gilbert Chemistry Set. (We began to see A. C. Gilbert as a sort of Steve Jobs figure, looming over our childhood from afar, a man we would never meet personally but who maintained a great influence over our lives.) A chemistry set in the 1950s was quite different from the sets we can buy today for our grandchildren. Modern sets either contain no real chemicals at all, contain very few of them, or contain them in such minute amounts a child can't do any experiments of any real value. Ours were different. They contained over 100 chemicals in enough quantity to cause a real mess, blow something up, or melt a hole in something. We were able to make glass, rubber, plastic, gunpowder, detergents, fuels, and just about anything else. We could create flames of any color, launch rockets in the back yard and mix inks and paints. We could make soap, batteries and oil. Somehow our parents who bought us these sets gritted their teeth and overlooked the fact that there was real danger lurking. Almost every one of us set off at least one explosion, either in the kitchen, garage or our bedrooms. Almost every one of us gummed up the kitchen or basement sink at least once. And almost every one of us destroyed several shirts. We were bright enough to follow the directions and wear safety goggles and stand back so none of us blinded ourselves or inflicted serious injuries, although occasionally we would show up at school with burn marks on our hands or arms. |  |

|

Like the Microscope and Erector Sets, we took all this for granted. We just thought it was fun. What we didn't realize was that the lab procedures, chemical formulas, weighing and balancing, "reading" of color to see what reaction took place, were all serious scientific skills. The very thick Introduction to Chemistry books that came with these sets taught us about molecular weights, atomic structures, and balancing equasions years before we would learn those things in school classes. We thought it was neat to doodle with those formulas and equasions on long Winter evenings. Then, when Dr. Rogers taught us the same lessons in junior high, we were thoroughly familiar. Some of us received the bigger sets initially, and some of us bought the add on packages later. But the Nuclear Chemistry units introduced us to Radioactivity (luckily, we worked with low levels). We created objects that glowed in the dark. We tested our basements for radioactivity. And we learned about half life and decay as a means of measuring ages of things like rocks or antiques. We unpacked samples of Uranium and experimented with them. We studied Strontium 90. At ages 10, 11 and 12, we were way ahead of the curve. |

| Even in grade school, we had our share of parties and other celebrations at each others' houses. Here is Albert sitting on a balloon to break it at a birthday party. At right is Jim and in the back is Nicky. The girls would have sleepovers while the boys mostly camped out in each others' backyards or in the woods up at the edge of town. |  |

|

The dangerous band of desperados includes Patrick, Donnie, Albert, Jimmy, Dale, Nicky and Steve. Notice how five of the seven are dressed in cowboy gear. Also notice how, at a birthday party, the main gift was a book. Grade school boys back then read series of novels about Tom Swift, The Hardy Boys, The Lone Ranger, Tarzan, Mother West Wind and Uncle Wiggly. Girls read similar series about Nancy Drew and The Bobbsey Twins, but they also read the Mother West Wind and Uncle Wiggly books. Both boys and girls read the books about dogs and horses, especially Black Beauty, Flicka, Rin Tin Tin, Lassie and White Fang. |

|

|

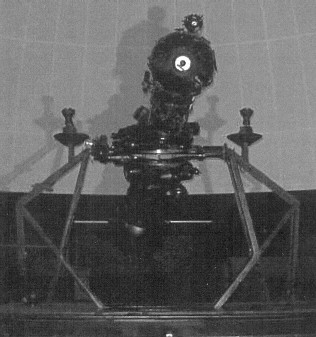

A major landmark during our school days was the Buhl Planetarium on the North Side of Pittsburgh. We were taken there on field trips, by our Scout units and sometimes by our families. At left is the Focault Pendulum, and right is the Zeiss Planetarium Projector, which we did not realize was the most famous unit of its kind in the world. We usually got a trip to Buhl once a year unless we got to go back as a birthday treat or for the annual Christmas train display. Many of us got our introduction to Geology with rock collections from Buhl. |  |

| During our entire time in school, the Buhl Planetarium was also the scene of the annual Allegheny County Science Fair. During our grade school days, we did not have a Coraopolis Science Fair. Instead, each teacher recommended students to Dr. Houtz, and he and Mr. Bolki from the junior high mentored them during the Fall and Winter, funding equipment they needed and bringing in special experts from Pitt, Carnegie Tech or local industry to advise them. Coraopolis won or placed in the top three every year we were in grade school. In fourth grade Dale took a first with his study of the oscillations of the Tilt a Whirl, Kenny took a first with his gas expansion experiment (his Dad worked for the Gulf Oil), and Danny took a first with his study of the ecology of a rain puddle. During fifth and sixth grades Dale and Danny conducted a two year study of the aquatic ecology of McCabes Creek. They not only took first at Buhl in fifth grade but in sixth grade first at the Pennsylvania State Science Fair at the Farm Show Arena in Harrisburg. |  |

|

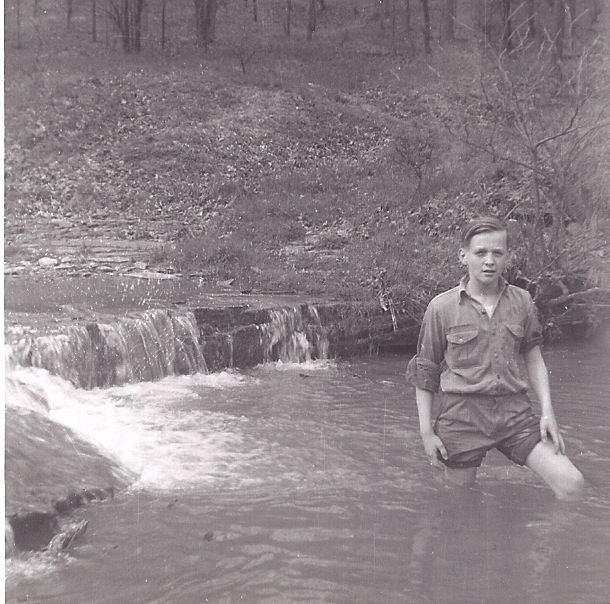

Dale and Danny in May of 5th grade collect samples on McCabes Creek below Wildcat Rock. They had their own microscope and chemistry sets at home, but they received Saturday instruction at Carnegie Tech in sampling methods and biochemical analysis and had been given hand me down nets and other collecting tools from the environmental sciences program there. A field representative from Carnegie Tech spent one Saturday a year in Coraopolis working with science fair contestants and took this photo. Their experiment was defined as a longitudinal study by the national science fair commission and the two intended to continue it for six years. But Dale's family moved to Robinson Township after sixth grade. Dale dropped science fair competition to concentrate on football, Scouts and academics. As a first place winner Danny was exempt from local competition and advanced directly to the state level. He continued to enter every year and won three more first places. This photo is courtesy of the Carnegie Mellon Archives. |

|

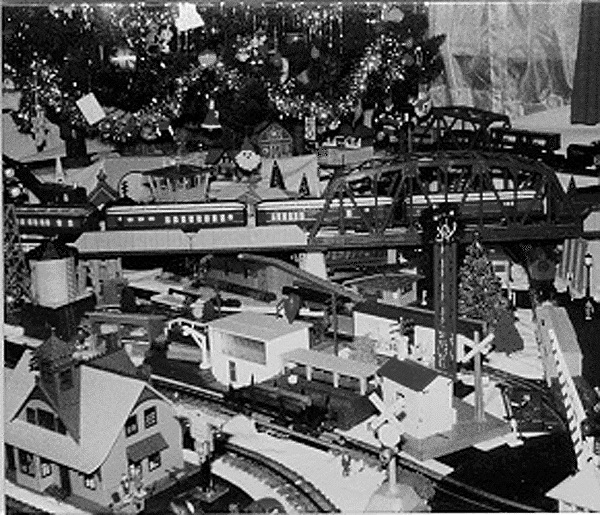

A byproduct of growing up in an industrial and railroad town was a love of trains and anything mechanical or electrical. Dads made sure boys had model train layouts under the Christmas tree. Work would begin on the train layout at Thanksgiving. We would visit each others' houses during Christmas Break and into January to see their trains. Most had Lionel but there were a few American Flyer and HO layouts. Michaels and the Hardware had train displays and sold equipment. Large layouts took up most or all of the living or dining room. A few were in the basement. |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

We would finish school at Memorial Day and not go back until the day after Labor Day. Not only were our Summers long, but they were hot and humid. Especially when we were too young for our parents to let us walk or bike to Dravo Pool or one of the swimming holes, we would cool off by running through backyard sprinklers. Sometimes we'd run through our own. Sometimes we'd get together at one of our classmates' houses with several other friends. Watching television was not an option. When these photos were taken, none of us yet had tv sets. Or air conditioning. |  |

|

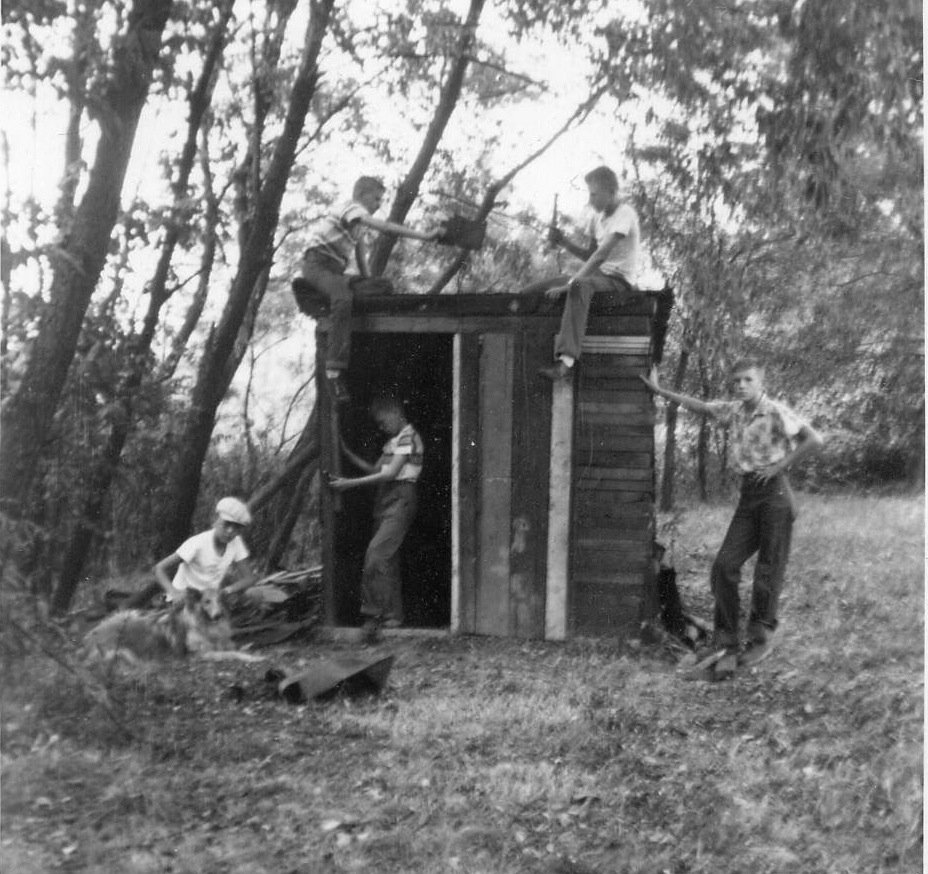

For boys going to Lincoln School, one of the most memorable finds of our grade school days was The Old Caboose. We found it when rather than hiking out the railroad tracks to go skinnydipping at The Deep, the guys living up on Vine, Devonshire, Edgewood, Cliff, Grace and Ferree Streets just cut down over the hill through the woods below Sacred Heart and the Felician Sisters Convent. Down there, in a gulley below the rail road tracks, concealed by trees all around, was an old caboose. It was a great mystery. Had it fallen over the hill? Did they lower it down by a huge crane and just abandon it? Did there used to be a track down there which they pulled up and left the caboose? Why did they abandon it? It had a symbol on it from another railroad. Why was it out here along the Montour Railroad if it was not a Montour caboose? How long had it been here? Did somebody own it and could we claim it? Was it safe to go in? Was it legal to go in? During our years in 4th, 5th, 6th and 7th grades The Old Caboose was the scene of many an adventure. It served as a fort, house, Alamo, ship, space station, tank, headquarters and any thing else we needed for the game of the day. |

One of the more epic achievements of our time in grade school was David's construction of a scale model of the Eiffel Tower. Mrs. Clark (who became Mrs. Tucker when she married at Christmas) allowed David an hour a day while we were working on other material, and he set up a table in the corner of the room. Today, you can buy models of the Eiffel Tower from Leggo (plastic) and Heller (wood). Not in 1953. David obtained 3 x 6 poster sized photos of the tower and converted them to scale drawings on poster board. He then bought strips and sheets of balsa wood from Michael's Hobby Shop on Mill Street. He used an Exacto knife set, which had a dozen different gauge razor blades inserted into a metal handle, to painstakingly cut the sheets and strips. They had to be pinned down to the poster board and glued into place to dry. He had to make four different sides, then raise them, brace them, and glue them together. The tolerance was almost zero. If he made any error on any side, the sides would not meet, and he was dealing with curved surfaces. As the project neared completion, the whole class was caught up in the suspense of whether or not he could bring it together. When it all fit, everyone cheered. Dr. Frank Braden came by from his office a block away and took a few photographs, one of which is shown here at right. At the end of the year David's older sister Gretchen helped him carry the model to their home, which fortunately was only across the street and down three houses (The family moved from their Hiland Avenue home that Summer). Both Doctor Braden and Mrs. Tucker told David he should become an architect. He did. |

|

|

One of the programs Harry Houtz and Helen Tussey created for us was the Summer Reading Program at the Public Library. For every book you read you got a new feather for your headband. Eventually, if you read enough, you had a headdress extending all the way down your back, as Jacquie does here. That's her brother with her. Notice the brick street. |

|

|

From Kindergarten on, we always wrapped up each school year with the annual Kennywood Park Picnic. It was a spectacular way to begin Summer Vacation. We bought tickets at school for half price. The whole town went. Parents took a day off work. Some parents drove. But first the train, then the trolleys, and finally Shafer buses, provided shuttle service for others. Many of our parents took picnic baskets and reserved a table in one of the huge pavillions. We would arrive at the park around noon and stay until it closed at 10 pm. In Kindergarten we were pretty much confined to Kiddieland rides plus the Train, Auto Race, Rockets, Boats, The Old Mill and Carousel. We had to be a certain height to ride the others. It became a matter of pride as, one by one, we grew tall enough to be allowed. We all loved Kennywood and knew it was an epic experience but we didn't realize it was the number one amusement park in America, with three of the nation's top 10 roller coasters and a dozen more rides ranked either number one or somewhere in the top 10. |

|

|

|

|

|

During fifth and sixth grade, a new piece of furniture began arriving in our houses : Television. It was black and white and we got three channels which went off the air at 10 pm. The kids shows we watched were Kukla, Fran & Ollie, Howdy Doody, Lassie, Roy Rogers and Captain Video. Our favorite character was Tobor, the robot who was always the villain in Captain Video. Every time they mentioned Tobor, the captain let us know that was Robot spelled backward. Supposedly Captain Video was in charge of the space ranger force but in five years we only saw one ranger. The show had three sets : one on the ship, one in the cave, and a rock on the planet Mysterius. |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

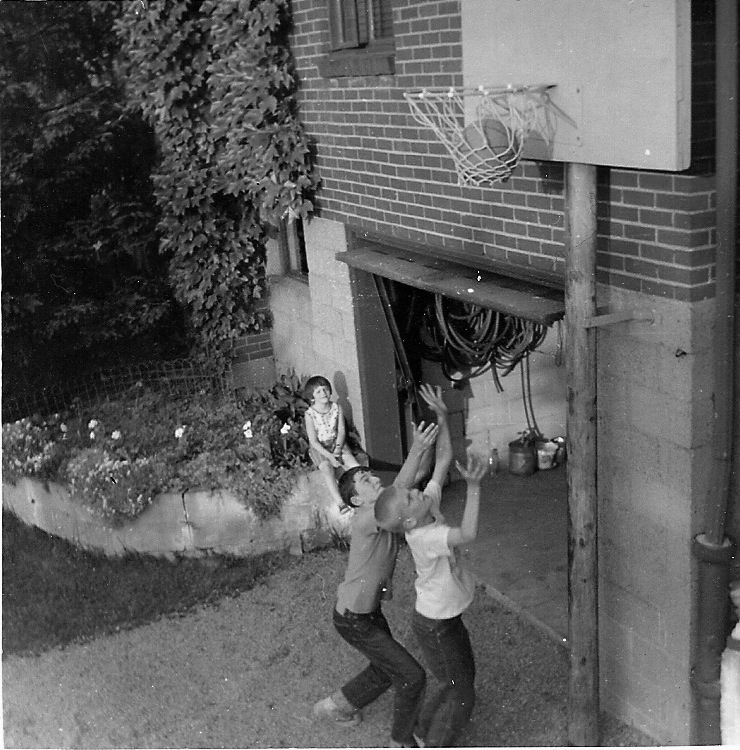

We started playing basketball in our driveways. The grade schools did not have indoor gyms, but during recess, at lunchtime if we got back in time, and after school, we would play on the school courts. Lincoln had the best grade school talent in town. Dr. Houtz' top floor office window looked down on our court just behind the school. One day he came out to our court, knelt down to be on our eye level, and asked us if we were interested enough in basketball to practice and play as a team if he found us a coach. After an enthusiastic response, he hired Joe Jewart (below left) from the junior high. The starters were Bo, Danny, Dale, Dick and Sleepy with Al, Ed, Kenny, Vite, Chuck, Donnie and Phillip as reserves. Since the WPIAL did not sponsor grade school competition, we registered as an AAU team. We played games against Bellevue, Sewickley, Aliquippa and Ambridge. In a one day tournament we beat teams from Central, McKinley and the YMCA. At the AAU 10 and under Tournament at Fitzgerald Field House at Pitt, we won four games to take first place. Dick and Danny made the All Tournament First Team and Sleepy made the second team. |

| The first team included Brian Generalovich of Farrell, David Sauer of Avonworth, and Jimmy Chacko of Charleroi. The second team included David Montgomery of Fort Couch, Bucky Pope of Crafton, Bill Hennon of Wampum and Willie Dean of McKees Rocks. That's Willie at right too late to stop Dale's pass to Danny on the fast break at Fitzgerald Field House. In our first big organized basketball experience, these names didn't mean much to us, but as we got into high school they would. Willie ended up playing quarterback and point guard for McKees Rocks. Dale and Vite would bulk up and play high school football, but they were outstanding basketball players. Note the "Power Ked Junior All Star" shoes, supposedly an orthopedically approved children's athletic shoe the AAU recommended until kids moved up to Converse. |  |

|

We were 50 years ahead of our time in our baggy uniforms, but it wasn't because we were cool. Since we were not actually sponsored by a school, we had no budget and parents had to pay for uniforms. To save money, Coach Jewart (left) ordered uniforms directly off the shelf, with no lettering, just numbers. But youth basketball was not big in the 1950s, so companies didn't make small sizes. We were all too short and skinny for the uniforms. Our mothers used safety pins to help the pants fit tight enough to stay on, but the legs were still far too big. We vaguely sensed how comical we looked, but we were playing basketball so we didn't care. Coach Jewart was a great coach who should have been head coach at the junior high. He had played high school and college basketball, unlike Mark Holpfer and Frank Letteri, who were football men. Jewart taught us a 1-2-1-1 press, 2-3 and 3-2 zones, and man to man defenses. We alternated 1-3-1 and 2-3 offenses and used a three lane fast break. Whichever side the rebound came off on, that guard went to the center circle while the opposite guard streaked downcourt. The photo above shows Dale taking the outlet pass from Bo and relaying it down to Danny. We probably did not have the best talent in Western Pennsylvania but were probably the best coached team. We beat Rox Bottoms 30-24, Langley 28-25, Duquesne 33-30 and Charleroi 35-33 for the championship. |

| When the Allen brothers transferred to Wampum, we moved Ed and Vite into their spots and continued playing under Coach Jewart in 5th and 6th grades. Danny played point on the 1-2-1-1 press with Dale on his left and Ed on his right, Bo at center court and Vite at the other foul circle. In halfcourt, we either played man to man or zone. In the 2-3 we put Ed and Danny on top with Vite in the middle and Bo and Dale on the sides. In the 3-2 we put Danny at point with Dale and Ed on the sides and Bo and Vite on the lane. On offense, in the 1-3-1 we used Danny at point, Bo in the middle, Ed and Dale on the wings and Vite down below. In the 2-3 we used Ed and Danny at guard with Vite at center and Bo and Dale at forwards. We stepped up our schedule, playing a full 13 regular season games, all away since we had no true home court and could not use the Y floor on weekends. In two years we went 24-2 in the regular seasons, won the county AAU title one more time and lost in finals once, for a total record of 31-3 total record. The two regular season losses were to Midland and Avonworth. The tournament final loss was to Farrell. Ed and Dale were our leading scorers, Bo and Vite our leading rebounders, Ed and Danny our leaders in steals, almost all off the press, and Danny our assist leader. Kenny was our sixth man but scored winning last second baskets against Springdale and Fifth Avenue. |  |

|

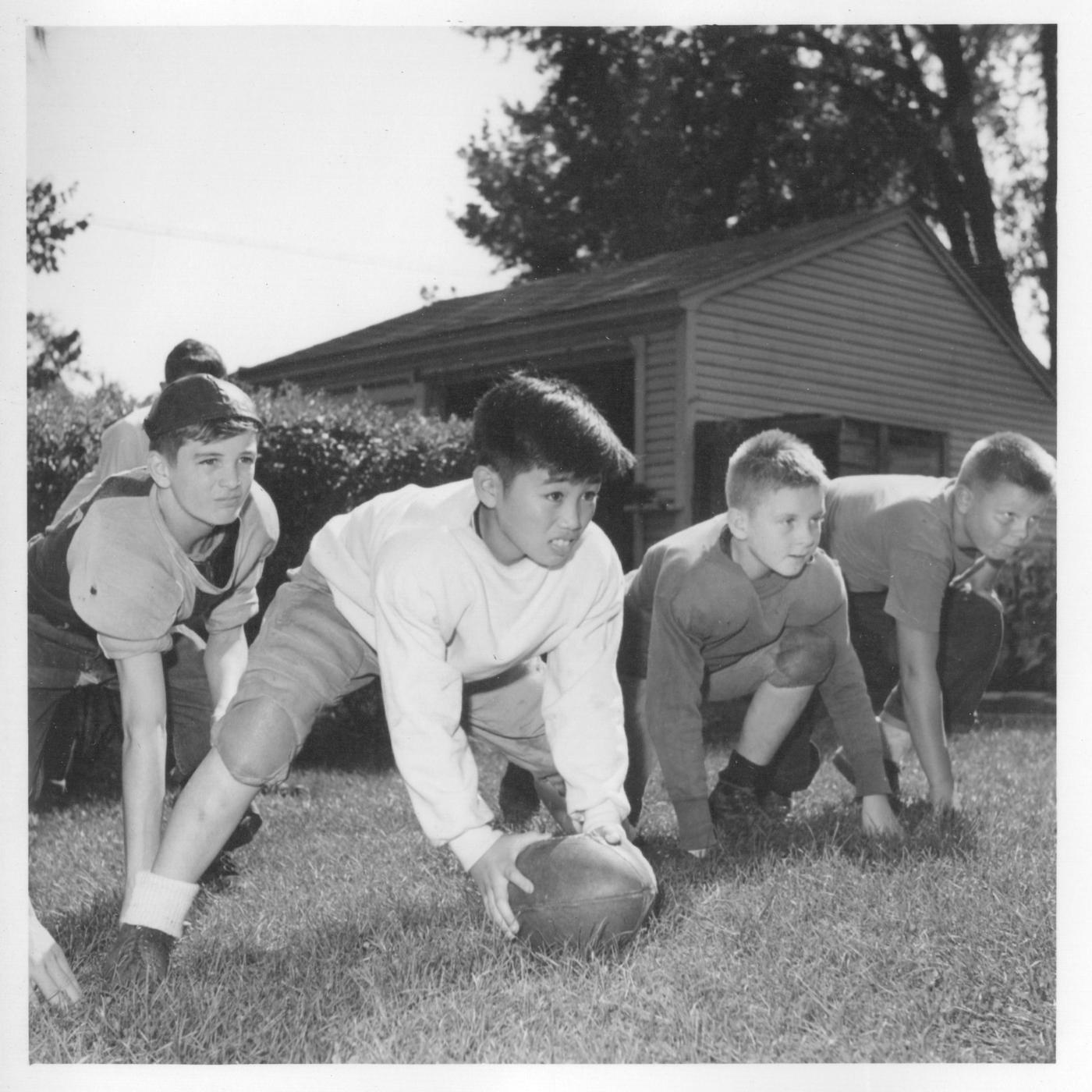

| We played football in big backyards, vacant lots, down at Ewing Field when baseball was over, and up at the Stadium when the field was not being used by the high school. Each neighborhood had a team and we played each other home and away. There were teams from Montour Hill, Below The Tracks, Central School Area, The Heights, and West End. Sometimes we'd challenge a team from Moon or Neville Island. Central had the biggest enrollment so it was no surprise it had the most football talent. By sixth grade we were all vaguely aware that the best players in town were Nick, Ange, Dom, Jerry, Jimmy and Vite. Everyone took turns playing various positions. We coached ourselves. The boundaries between neighborhoods were approximate, so players on the margins sometimes played for one team, sometimes another. When we hiked or biked across town, we settled in for some serious football, and games often lasted all day Saturday or half a day Sunday. Occasionally one of The Big Kids, such as Mole Lanza, Sam Maxwell, Foge Fazio or Fred Trello would stop by and give us a little coaching. We designed our own plays. We didn't have goalposts so we always ran or passed the extra point. Rarely did anyone have a helmet or pads, but somehow none of us ever got seriously injured. If someone took a hard hit and couldn't get up for a while, we'd call time out and everybody would go get a drink while the injured party recovered. We'd play in rain, mud, snow and cold. When we were seniors, it all paid off. |  |

|

|

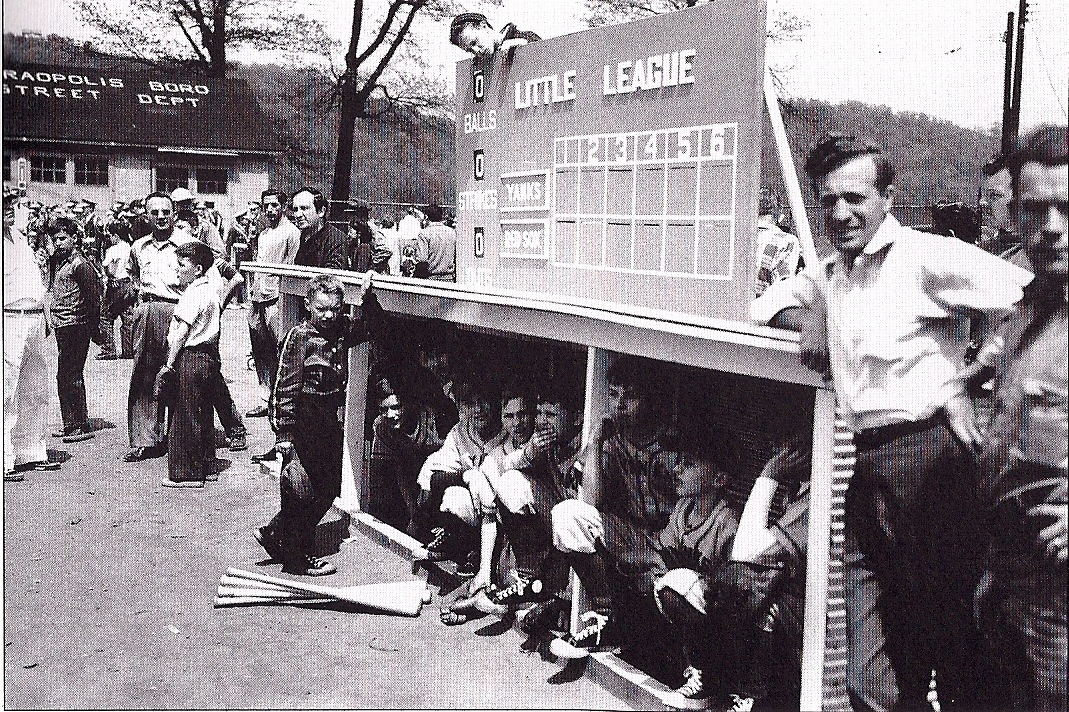

Football and basketball may have been bigger in high school, but at the elementary level baseball was the big thing. We played it at recess at school. We played it in yards, and sometimes we played a version of it out on the streets. We adapted the rules according to how many players we had, and what the field parameters were. We had Train Rule Doubles, Car Coming Doubles and Broken Window Outs. In really tight yards, we'd use a wiffle ball, a plastic ball with holes in it so it wouldn't travel very far. When one kid had to go home to eat or cut the grass, somebody would take his place and the game would go on. But the main action was down at Ewing Field, where we had one of the finest Little Leagues in the county. There would be tryouts every Spring and teams would be chosen. The Record sent reporters and photographers down to cover the games, there was an announcer, and the dugouts were better than most. It was a pretty big time program for a bunch of grade school kids. Looking back through old Record microfilm, the names of Ronnie, Jesse, Nick and Joe keep showing up. The field has been renamed in honor of Ronnie. |

|

| From the time we were old enough to walk, most of us had a father, uncle, grandfather or neighbor who took us fishing down on the river. The best places were where the four creeks emptied into the river. They created sandbars where we could set up lawnchairs, a cooler (root beer for us, Rolling Rock or Duquesne for the adults) and the portable radio (for the Pirate game). We caught mostly catfish, croppie and various kinds of perch, but there would be an occasional eel. We'd while away the evening with the cool breeze drifting off the river, the waves lapping at the bar, and an occasional raccoon or deer emerging from the trees for a drink. By the time we were in college, we learned that the river was polluted, the fish in it contained dangerous toxins, and we should never ever eat them. According to the studies, we had already eaten enough to kill us 10 times over. Now we're all in our sixties. We must have been tougher than we thought. |  |

|

|

As we got older we could take canoes or john boats out on the river ourselves. There were several great campsites up and down the river we could paddle or row over to. For a weekend, we could fish, swim, and pretend we were Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. Some of our families also owned larger boats which on a Saturday or Sunday we would go for longer cruises on. The best way to celebrate Fourth of July was to go out on a boat, drift down to the lower end of town, anchor, and watch the fireworks. This was perfect when we were in grade school because they set them off from Ewing Field close to the river. As we got into junior high they moved them up to the Stadium. From a boat on the river we could still see them, but they were further away and not as loud. This shot is taken from a campsite at the tip of the island looking across at Coraopolis. We did most of our grade school adventuring between this spot and Groveton. The water was shallower, warmer and calmer, and the river was not as wide. Below this spot, it was four times as wide, much deeper, colder and the towboats set up dangerous undercurrents and surface waves. The other side of the island, facing Ben Avon and Emsworth, was similar to that. But this home bank stretch was more like our private lake than a river. We learned to swim, fish, canoe and boat here. |

|

Girls were enrolled in piano lessons by their mothers while we were in grade school. Each area had its own teacher. Lincoln area girls went for lessons to Mrs. Buzza's house on Hiland Avenue, shown here at right. The house sat high on a hill above the street, looking out over half the town. A lesson would last an hour and a girl would go for one lesson a week, usually taking cash in a sealed envelope to pay Mrs. Buzza. Central school girls took their lessons from Mrs. Xxxxx. McKinley girls took theirs from Mrs. Xxxx. The girls were expected to practice at home an hour every evening. Some girls dropped out after sixth grade, some after ninth grade, and a few continued on all the way through high school. Regardless of how seriously the girls took the lessons or how long they stayed with them they grew up with a thorough knowledge of music, which later many of them applied to various instruments in band or orchestra, or to vocal music as part of the choir. |

|

|

In fourth grade, most students were enrolled in band. We started during the Summer. We conferred with our parents and teachers and chose an instrument from woodwind (clarinet), brass (trumpet), percussion (drums), and specialized instruments like cymbals, triangle and bells. We began by learning to play a tonette, bugle or block of wood. We met Sam Carson, Sam Yahres and Ed Schores, who would direct our band and orchestra for eight years. It is amazing to recall the songs we played on our tonette, bugle, wood block, cymbals, bells and triangle. Eventually we advanced to clarinet, trumpet and snare drums. We were supposed to practice at home for an hour each evening. Our parents were encouraged to enroll us in private lessons, which were given by several instructors in town. Most of us began by renting the instruments ("to see if we liked it") but after a year most parents began purchasing one, usually from Mr. Sworgel from Wexford, who also supplied the school. We called it Band, but we did not march, so what we had was really an orchestra. We would not begin marching in the "big band" until seventh grade. Mr. Carson, Yahres and Schores invested this extra effort because a school as small as Coraopolis needed to build a strong foundation early if it was to field a competitive band. They wanted those needed numbers. We would find out many years later that Dr. Houtz pushed this effort because he had evidence suggesting early music education improved math skills. He was one of the first administrators to accept this theory. Today, it is a common assumption among educators.

|

|

| We were blessed in Coraopolis to grow up with woods all around us. Thorn Run Hollow began at the West End, along Thorn Run Road, extended along the outer edge of town bordering The Heights, then continued deep into Moon Township. Omlors Woods began along Montour Street and followed McCabes Creek below Stadium Hill out past Charlton Heights to Pleasant View. Moon Run Hollow began at Groveton and extended deep into Robinson Township. And there were smaller woods down along the river and occupying steep hillsides. All of us lived within walking distance of a patch of woods. We took this for granted, and both boys and girls spent time in one or another of these woods. Girls picked bouquets of violets every Spring and brought them to school for their teachers, collected different kinds of leaves, and learned to sit quietly leaning against a tree and watch for deer, birds, fox, coon, and once or twice a year a wildcat. Boys climbed trees, explored caves, built dams along the many creeks, and built lean tos and other shelters for "camps." By the time we were in fourth grade, most of the boys were hiking all the way out the various creeks and camping out. They were also taking the girls with them on long day hikes. Often the girl would bring the lunch for both of them and they'd spend a long mid day on Red Oak Hill, Wildcat Rock, McCabes Meadow, or Indian Ridge Point. One favorite activity on these trips was berry picking. Every woods was full of strawberries, blackberries, blueberries, raspberries, black raspberries, eldeberries and gooseberries, and in an hour or so two kids could fill a basket, bucket or Giant Eagle bag for the trip home. We learned to make Sassafras tea from the roots, Chickory coffee from the leaves, and how to prepare and eat Wild Carrots, May Apples and other wild edible wild plants. By the time we got old enough for Girl Scouts and Boy Scouts, we were ready. |  |

|

|

|

|

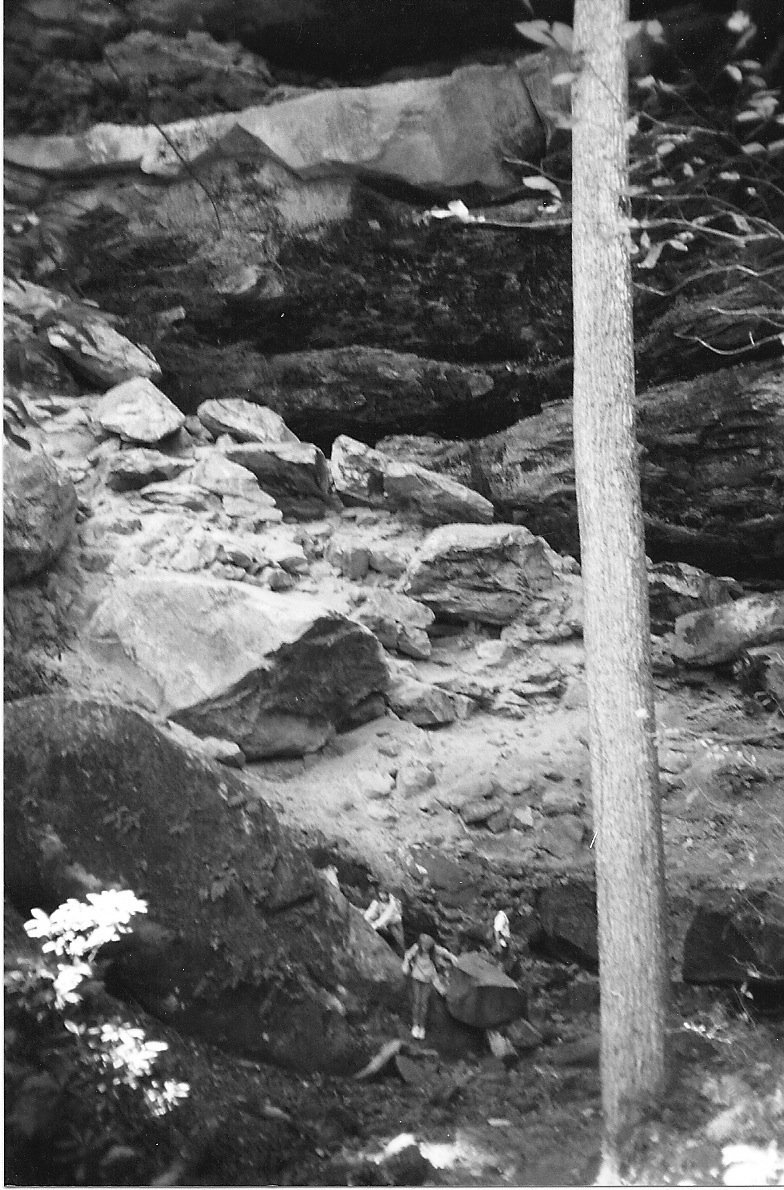

McCabes Meadow was an abandoned farm at the head of McCabe's Creek. It was actually in Moon Township but it was a favorite place to hike out to for lunch. There were plenty of wildflowers and six kinds of berries. And then there was Wildcat Rock, which loomed over our grade school days like a symbol of adventure. It was actually quite close to town within a reasonable walk of everyone. The three girls at right (very small at bottom) are playing at the very base of the cliffs, further around from the Girl Scout Lodge, on the Charlton Heights side. Parents often told kids, especially girls, that they could go to Wildcat Rock but not to climb up on top or enter the caves. Some of us obeyed these orders. Others ignored them. The fact that we escaped disaster was probably a major miracle. |  |

| One advantage of growing up near all these woods was that when we played Cowboys & Indians, War, Davy Crockett, Daniel Boone or Peter Pan, we had realistic backdrops. We could play out there all day Saturday and never bother the neighbors. Unlike more confined kids in more urban areas, we could expand our games to range across miles if we wanted to. But there was something else. If no one else was free to go with us, we could take our dog and head out into the woods on our own. Year by year, we grew comfortable going further and further out. At a very young age, most of us developed a sort of self reliance. We enjoyed being with our friends, but we were also quite at ease being alone, a mile or so from the nearest house. It was like a huge communal yard out there. We knew the names of every tree, every bird, every animal, We didn't need maps to find our way around. Few of us had televisions during those early years. The woods was our TV. It was always entertaining. It could be whatever we wanted it to be. It is not surprising one of us earned his Ph.D. in Forestry and spent his adult career in the Forest Service and two more spent theirs as Boy Scout administrators. This scene is in Omlors Woods. |  |

|

Pumphouse Creek Woods was not nearly as big as the others, but it was nestled between Devonshire Road, Buckingham Place, and Cliff Street. It was just below the yards of Kenny, Jimmy, David, Ed, Alex, Big Chuckie, and Donnie. They could play in the woods and hear the dinner bell ring on their parents' back porch. Pumphouse Creek, seen here at left running muddy after a rain, was not as big as the others, either, but it was the site of our most famous dam, one we spent weeks building and which lasted for years. Shown here is a smaller dam. We were always damming up streams. We had a fantasy picture in our minds of building a dam which would back up the water deep enough to swim in, but we never achieved that. The only swimming holes were The Deep and The Chute, which occurred naturally. |

|

| There were several Girl Scout units in town. Today Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts schedule many activities together, but back in the 1950s we still operated separately. Coraopolis Girl Scouts had a huge asset : a lodge built in the woods just below the Stadium, reached by coming around the hill from Coraopolis Park. They were close enough to easily schedule weekend or even weeknight events there, but far enough out of town to make an overnight or weekend event seem like it was a big adventure. Girl Scouts focused more on domestic skills and less on outdoor adventure than the Boy Scouts, but they still learned their share of camping and outdoor skills and got into the woods several times a year. Way back in the fifties they were already famous for the annual Girl Scout Cookie sales campaign and many of our parents bought a box or two. Some of the boys even bought boxes on their own. Girl Scout units conducted annual cleanup projects and other public service events. The girls pictured here are conducting a cleanup in the vacant lots just north of Route 51 in the East End, up the side road from the old Montour Railroad Yard. The buildings and structures in this photo have long been torn down, but the utility lines remain. The water tower in the distance is up on the hill by Sacred Heart School and the Felician Systers Convent. |  |

|

1950s Winters were long, cold and snowy. We spent evenings and weekends sled riding. The borough would close off streets and ash the bottoms. The biggest weather event was the Big Snow of 1950. It started snowing the day after Thanksgiving and snowed five days. When it was done we had five feet. It was the only time school was closed. We got a week off. Our parents shoveled paths down the middle of streets so mothers could get groceries. It was a pretty hard week for the adults, but we loved it. We kept hoping for another big storm. We got lots of lesser snows, and plenty of sledriding, but we never missed another day of school due to snow. At right Dale & Saranna are on George Street just above Vance Avenue. At left Chuck and his mother are on Chestnut Street. |  |

We were blessed with a whole decade of White Christmases. It was easy to imagine the sleigh up on the roof because we always had snow. Two weeks out of school to enjoy the holiday and go sledriding. Most of us got sleds for Christmas presents. Some got the newfangled saucers or skeds, but the Cadillac was still the Flexible Flyer, seen here. It had oak slats and stainless steel runners and outran everything else in town. We could ride it laying down steering with our hands or sitting up steering with our feet. We could even ride it double. There was a whole set of tricks and skills to sledriding. We learned to run a piece of emery paper over the runners to remove any rust, and to pack a ball of ice and rub it along the runners just before a racing run. We learned to lean with curves to help the steering and use our feet for braking. It took a while to get all bundled up so once outside, we tended to keep sledriding until our feet were frozen. Then we'd come in and prop them on the vent or radiator while drinking our hot chocolate. A lot of us graduated to skiing in our 20s, then, with our kids, returned to sledriding and remembered how much we still loved it. And Flexible Flyers are still the best. |

|

|

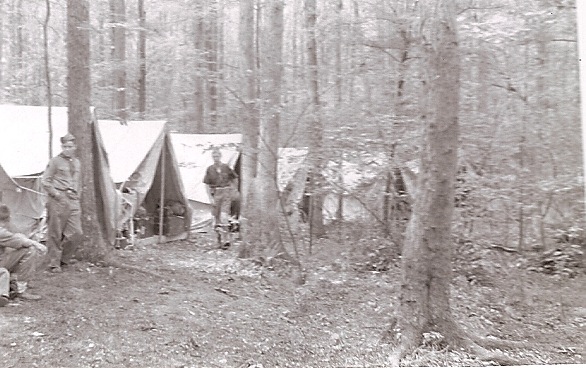

| One of the great advantages of growing up in Coraopolis was the outstanding Scout programs we had. Most of the churches combined their resources into Troop 133, hosted by the Presbyterian Church. By the time we came along, this had evolved into a strong program for boys aged 11-18. The Scoutmaster was Ferguson Ferree, who lived only one house down from the high school. He had worked his way up as an officer in the Army during World War II, then retired to accept a position at Pitt. He ran the troop as a military unit with an emphasis on discipline, leadership training and a well laid chain of command. Many boys remained in the troop through high school, then came back and helped during the Summers when they were in college. Three of our class went on to serve as Scoutmasters themselves, and BillR became a full time Scout executive. Almost every boy who grew up in Troop 133 continued hiking, backpacking and canoeing all their adult lives. The photo at right shows John as a Senior Patrol Leader checking the tents during free time on a typical camping trip. |  |

|

Boy Scouts spent two weeks every Summer on a major camping trip. Often they went to Camp Tionesta, a Scout Outpost in northern Pennsylvania near Cook's Forest. We were an advanced unit, fully certified in woodcraft, so each Summer the camp would allow us to create a whole new campsite. We would build bridges and entranceways as shown at left. Several of our classmates earned the rank of Eagle, highest available. The best of those were also admitted into the Order of the Arrow, an elite corps of highly trained outdoorsmen. In addition to these established Scout camps, we would also go on major expeditions to national parks, such as Gettysburg, Valley Forge, the Adirondacks and Shenandoah. We did more than "play in the woods." We were trained in first aid, emergency medicine, disaster response, and search and rescue. |

But the majorityof our activities were held over weekends during the school year. We hiked and camped the woods around Coraopolis until we knew them like the back of our hands. This particular scene is down the hill from where Stan and Marianne now live. A few times we were hiking out in those woods and were stopped by armed patrols who told us we had wandered onto the back end of the Nike Base. Even on day hikes, we all had to fix a hot lunch. On longer trips, we had to fix three meals a day. Boys didn't take Home Ec in school, but we learned how to cook through the Scouts. We didn't have GPS units yet, so we all had to learn to read a topo map and use a compass very, very well. We also had to learn to "live off the land," fixing entire meals from the plants found out there in the woods. When a lot of us went into the military, after a few days of basic training, the drill sergeant would single us out. "You," he would say, "You were in the Boy Scouts." We would admit that, yes, we were. They would send us on up the line, skipping much of the basic instruction. Wayne, the boy in the striped t shirt at right, was actually from Robinson Township but came into Coraopolis to participate in Troop 133. |

|

|

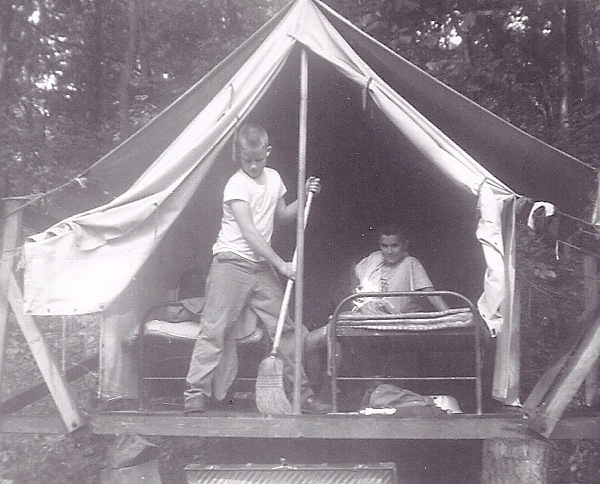

This stellar bunch is the Flaming Arrow Patrol of Troop 133 of the First Presbyterian Church. Several of them are in other grades, but from our class are Jimmy, second from left, Danny, in front of the Scoutmaster, Bob in glasses, Dale far right in front row, and John, partially obscured by Dale. The Scoutmaster is Ferguson N. Ferree, who twice was recognized as Pennsylvania Scout Leader of the Year. This photo is taken in June at Camp Hubbard in basecamp. The "wall tents" were heavy, rugged shelters with wooden floors and cots. From there, we would hike or canoe out on expeditions, carrying lightweight pup tents, air mattresses and sleeping bags. Here in camp, we would prepare full scale meals with cast iron cookware over semipermanent fireplaces. Out on expedition, we would use freeze dried food, aluminum cookware and powdered milk, cooking over campfires. At basecamp, we would receive instruction in archery, riflery, swimming, lifesaving, emergency medicine, botany, zoology, and heavy duty wilderness engineering, which involved building bridges and towers from logs and heavy ropes. The Boy Scouts were modelled on the military. A typical troop had four patrols. This was only one of Troop 133's four. Note the hand carved owl and Indianhead neckerchief slides on Danny and Dale. |

We paid $26 for two weeks at Scout camp, and then spent much of our time there hard at work. We had to keep our beds made, floors swept, campsite free of litter, dishes washed and garbage properly disposed of. We had to build the fire four times a day, cook the meals, and wash the dishes. And we had very little free time. Almost every minute was scheduled. The swimming, lifesaving, first aid, emergency medicine, search and rescue, and wilderness medicine classes were especially demanding. Archery and riflery classes were relaxing, and we had a "free swim" hour every day. But canoeing and wilderness engineering classes were usually in late morning and left us quite ready to sit down at lunch --- AFTER we built the fire and then fixed and served the lunch. At dark special classes like Astronomy and Night Biology met for an hour. Then, whether in base camp or out on expedition, we sat around a campfire and relaxed, but it was not unusual for several of us to excuse ourselves by about 11 and crawl into our sleeping bags, since we knew the bugler would sound Reveille at 7 a.m. It was essential to have a high energy level at Scout camp. If you didn't have one when you went, you developed one by the time you came home. Rain didn't matter much. We just pulled on our rain gear and the day continued as usual. Only lightning would cancel activities. |

|

|

|

|

| Our very first year in Boy Scouts was in 4th grade, and our first ever Summer Camp was between 4th and 5th grades. Three of the four Coraopolis troops went to Camp Hubbard that Summer. Above left, Dale pauses in front of his tent before moving in. These were U.S. Army Surplus Teepees. We loved them. This campsite was a beautiful hilltop with dense forest behind it and a sloping meadow in front. Center, we're stopped for lunch on a canoe trip and in the background most of us are wading out in the shallow creek. Right, Vite takes aim at the archery range. |

|

|

One of the bigger differences between how we grew up and how kids today grow up is that we were allowed much greater range of movement. Even in the lower grades, we were allowed to walk or bike to friends houses, to school or to places like the YMCA. We would walk from down in town up to friends' houses on the hilltops or from the hilltops all the way down to the Y, the Fifth Avenue Theatre or Ewing Field. In this photo, Carolyn relaxes on the back porch after hiking up the Cinder Steps with Carol on a Saturday afternoon visit to Danny's. In Winter, we would pull our sleds behind us and walk to the good sled riding hills, whether they were blocked off streets, Omlor's Woods, the Pump House, the Cemetery or Stadium Hill. For whatever reason, kids today are not allowed this much freedom of movement at this early an age. Maybe there's more danger out there. Maybe parents are more paranoid and too protective. Maybe kids are not as self reliant. But whatever the reason, our grandkids are growing up in a much more restricted environment. |

| We had a lot of fun and roamed around quite a bit, but life was not all a big adventure. We had work to do. Most of our parents took a dim view of childhood. As soon as we were old enough to walk around, we were expected to pitch in and help with the chores. That included raking leaves (as Lynette is doing at right), carrying out the trash, washing and drying the dishes, weeding the garden, sweeping the porches and sidewalks, making our beds, and anything else our parents thought we could handle. Most of us lived in households where a father went off to work and Mom spent the day taking care of the house. It was common practice for Dad to assign us tasks to be carried out before he arrived back at the house after work. Woe be to our classmate who did not finish that list of assigned duties. Considering the fact that we were in school much of the day and had homework in the evenings, we actually had very little free time. It was a wonder we found time for as much fun as we did. |  |

|

| Halloween in Coraopolis in the 1950s was a Very Big Deal. We decorated windows and doors at school with witches, crescent moons, ghosts, bats, black cats with arched backs, headless horsemen, skeletons, and headstones. We wore costumes to school and had Halloween parties, picking the best costumes, bobbing for apples and getting out at 2:30 to get ready for Trick or Treating. We went through our neighborhoods and as many other neighborhoods as we had time for. It was not unusual to find ragamuffins from below the tracks up on Montour Street or from Vine Street over on Neely Heights. We learned in art classes and scouts how to carve pumpkins and every house had at least one leering face on its porch. The night before Beggars Night was the Halloween Parade, which ended at the Borough Building. They built a scaffold and judges stand, divided the contestants into grade school, teenage and adult divisions, and chose the top three, who won awards of $100, $75 and $50. Churches held Halloween parties. There were costume parties in homes. With school, the parade, trick or treating, church and house parties, Halloween celebrations lasted a week. Among our most legendary costumes were Bonnie as Tinker Belle, Elaine as The Queen of Hearts, Lynette as Snow White, Karen as Alice in Wonderland, Kenny as Davy Crockett and Chuck M as Dr. Houtz. |  |

|

Left : Front : Janice, Emma. 2nd Row : Bill, Ron Tagliferri, Joe O. 3rd Row : Tony, John.

Right : Front : Jack K. 2nd Row : Joe O, John. 3rd Row : Joe C, Jimmy, Tony.

|

|

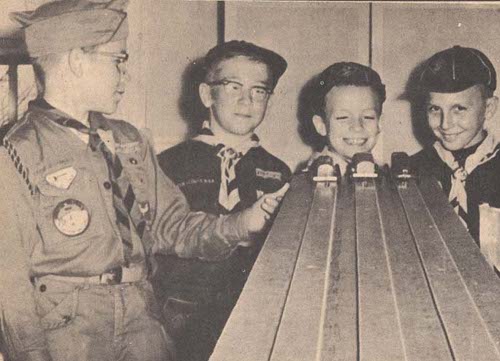

| One of the first "big time" events of our grade school years was the annual Pinewood Derby. We became eligible for this in second grade. Contestants received a standard kit which included a block of wood, two axles, and four wheels. We had to carve a car out of the block of wood, thread the axles, mount the wheels and fine tune the parts to reduce friction and allow the car to roll down a steep slope faster than its rivals. The competition was held at the Presbyterian Church, and the track was stored there the rest of the year. There was an automatic release mechanism provided by the national Boy Scout headquarters so all towns had the same starting procedure. |  |

|

We didn't realize this at the time, but the Pinewood Derby was a brand new event as we entered first grade. It was conducted on a trial basis that year, then as we became eligible in second grade it was in its first official season. Coraopolis had the only track in the area, so we also hosted entries from Moon, Robinson, Neville and Crescent Townships. So today, with the Derby half a century old, some of our class can say they were among its original contestants. Patrick won the first ever Coraopolis Pinewood Derby. He moved after second grade and Kenny won it when we were in third grade. They advanced to the County Derby at Buhl Planetarium but neither qualified for nationals. These photos make it appear the event was limited to Cub Scouts. Actually, the Cub Scouts sponsored it, but any boy who met the age and residency requirements could enter. |

The Power Line was a landmark for boys growing up in our era. It was a series of high steel towers running approximately along the southern boundary of Coraopolis from Robinson Township over to Mooncrest. They carried high voltage power lines. We would later find out the Power Line began on Bruno's Island, the Duquesne Light generating station, crossed the river to Stowe Township, and went all the way to Jones & Laughlin Steel in Aliquippa. A tractor sized riding bushhog came along once a month and cleared off the ground below the Power Line so maintenance vehicles could get in. This clearing was known as The Power Line Trail and was a kind of highway for grade school boys to get from Montour Hill up over Charlton Heights and down to Thorn Run Hollow. We were, of course, trespassing on Duquesne Light property, but at ages 8-12 we ignored such details. Not only did the Power Line Trail allow us to easily move back and forth along the edge of town, but it also allowed a gang of Mooncrest kids to invade our territory whenever they wished. This gang became known as The Legions of Mordor and were the Evil Empire we fought against at the age of nine. The year long rivalry, Capture the Flag carried to its logical extreme, became known as The Great Crab Apple War and was one of the epic memories of our grade school years. |

|

|

The Cliffs of Mordor rose from Route 51 to the back edge of Mooncrest. The word Mordor was an acronym from World War II. It stood for Mooncrest Offbase Radar Defense Officers Residences. An abandoned radar shack stood just at the edge of the cliffs and had been commandeered by the boys of Mooncrest as their clubhouse. Since they had boys living in residential units along the Power Line, it was not possible to approach Mooncrest by that route without being seen. Therefore, when we decided to invade Mooncrest as part of our year long war games, scaling these cliffs was our only access. We had a spy, Albert, who frequently spent weekends with an uncle up there. So Albert snuck out in the middle of the night, tied ropes to trees and threw the other ends down. We were then able to climb the ropes and surprise our rivals. In third grade, before we started playing other towns in football and basketball, this kind of competition was a very big deal. |

|

|

|

|

Carolyn pauses at the end of a long day in May of sixth grade at Central School. Like all of her Lincoln classmates, she had to go to Central for sixth grade because Lincoln was overcrowded. Carolyn was one of the sweetest girls in the Lincoln neighborhood UNTIL one of the boys started teasing her about having bird legs, which would send her into a violent rage. But she was one of the most adventurous of the Lincoln girls, being the first to ride the Jackrabbit (4th grade), Racers (5th grade) and Pippin (6th grade) at Kennywood at the annual school picnic, the first to participate in sports and games with the boys, and the first to sledride on the big hills of Vine Street and up at Omlors. Carolyn was always telling the boys that if she lived up on Montour Hill with big backyards like they had, she'd have a pony and ride it every day. She fulfilled that fantasy, moving to a Moon Township farm and breeding, raising, training and showing horses. |

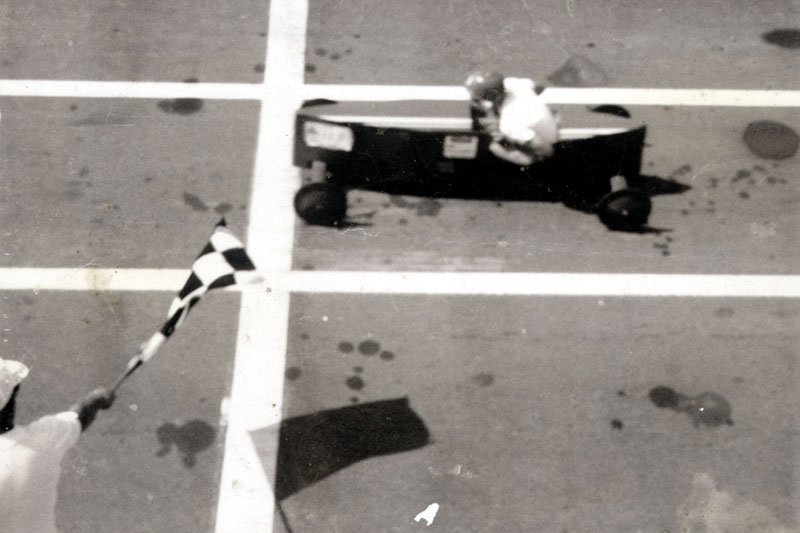

| One of the great experiences of our grade school years was the annual Soap Box Derby. Sponsored by Pete Myl Chrysler Dealership and the Coraopolis Jaycees, this May event required a boy and his father to work together building a race car that would compete in downhill races. The car had no engine; it was powered solely by gravity. Every town held its own local championships, with the winners advancing to Allegheny County Championships at Pitt and then to the Nationals at Akron, Ohio. Our local "racetrack" was the steep hill coming down to Route 51 opposite the Montour Railroad Yards. Police blocked off the street for two days, Friday for trial runs and Saturday for the elimination heats. The Montour Railroad had a special braking run built which looked like a modern skateboarding halfpipe. After crossing the finish line (below right) cars would go back up a steep hill to stop, then coast back to the level. Donnie won our local trophy two years in a row and went on to Pitt and then Akron, where the second year he lost a photo finish in the semifinals. Even those of us who didn't win learned a lot about design, construction, friction, weight distribution, drag, steering, wind resistance, inertia and momentum. Our first cars were pretty crude, but over the few years we learned how to make them streamlined, smooth and fast. |  |

|

|

|

| With our Chemistry Sets, Erector Sets, Microscope Sets and building projects like the clubhouse, caboose, and railbike, we had some great successes while in 4th, 5th and 6th grade. But one of our spectacular failures was our three year attempt to construct a submarine and use it to explore the river bottom. No matter what we did, we could not get it to hold out the water. Fortunately, we always tested it at the Groveton Boat Club, which was in the quiet, shallow and calm back channel. So except for the need for the test pilot to make a quick exit and swim back to the surface, and then for the rest of us to rescue the sub from the bottom of the river and haul it back home for another week's work, there was no lasting harm. But it was a serious blow to our 10, 11 and 12 year old egos not to be able to pull this project off. We got the plans out of a Popular Mechanics Magazine. It seemed simple. But we had to pedal and steer it from inside, and the openings in the steel drum where the steering and pedal cables passed through to the outside was where the water always leaked in. The most we could ever keep the pilot dry was about five minutes. We persisted in this project right up to the start of school in 7th grade, then finally abandoned it. Al and Phillip were our usual test pilots, being small enough to fit inside comfortably and exit quickly. The window in front of the conning tower is not visible. |  |

|